Introduction

Sustainable financing is growing in popularity as governments, businesses, and investors strive to address pressing environmental challenges through innovative financial mechanisms. Among these, green investment funds play a crucial role by channeling capital into environmentally responsible projects and enterprises. However, integrating sustainability into finance requires a robust regulatory framework to ensure transparency, coherence, and accountability in the markets.

The impact of regulations on green investment funds has become a central issue in both academic and political discussions. Regulatory frameworks shape the structure, operation, and outcomes of these funds by setting criteria for sustainable investments, imposing disclosure requirements, and establishing risk assessment standards. Specifically, aligning financial practices with broader sustainable development goals depends on the clarity and effectiveness of regulatory measures.

Exploring the regulatory frameworks governing green investment funds is more than an academic exercise but a key factor for the future of sustainable financing. In a world facing climate crises and social inequalities, effective regulatory frameworks can turn investments into a powerful tool for change. This report explores this critical issue, aiming to answer the fundamental question: how can regulations not only make green funds more sustainable but also inspire a global transformation of financial markets? The answer to this question will determine whether regulators and investors can collectively build a financial system that places sustainability at the heart of its mission.

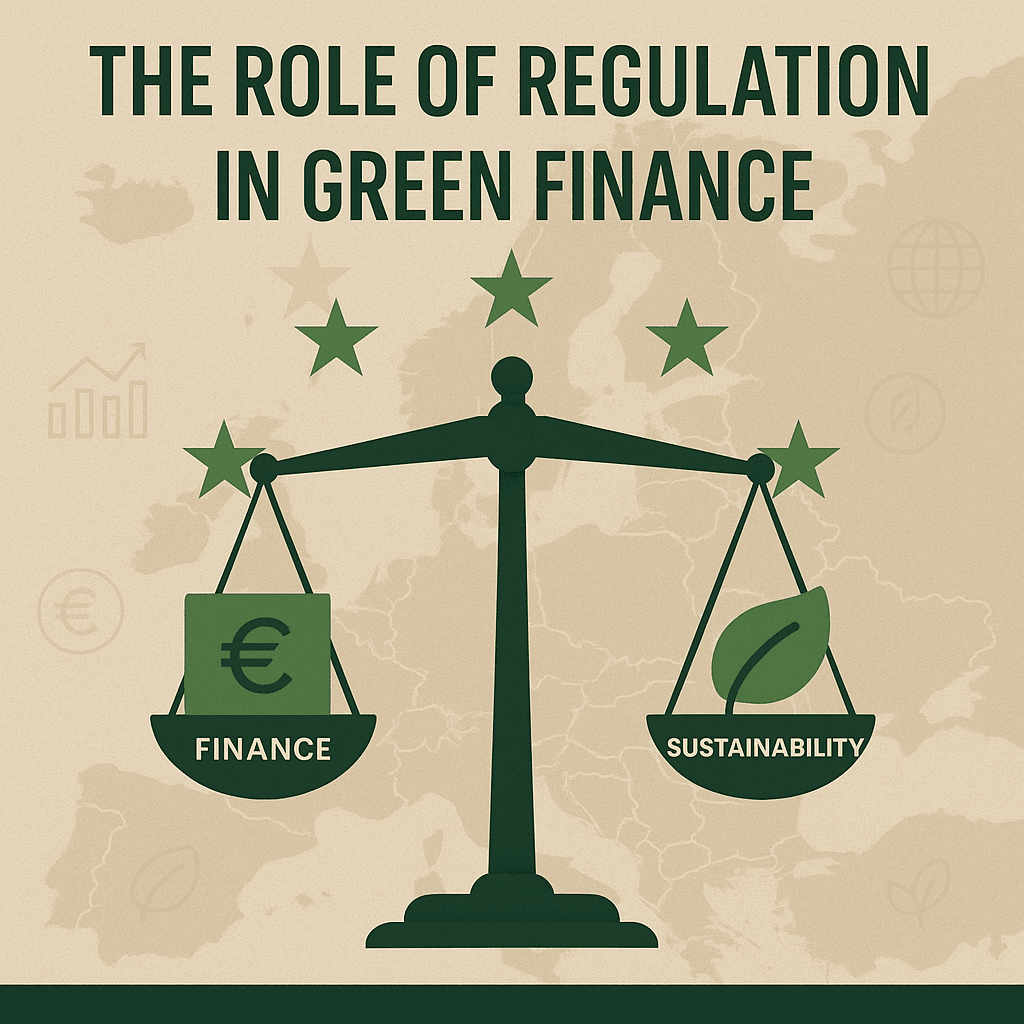

Green investment funds are becoming an increasingly important component of the financial ecosystem, with global sustainable investment assets reaching $35.3 trillion in 2020, representing 36% of total assets under management in major markets[1]. These funds combine economic returns with social and environmental benefits, setting them apart from traditional investment funds, which typically focus solely on maximizing financial outcomes.

Graph 1: Growth of Global Sustainable Investment Assets

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2020). Global Sustainable Investment Review.

These funds finance projects in areas such as renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, sustainable transport, waste management, and biodiversity conservation. These investments are part of global efforts to transition to a low-carbon economy and adapt to climate change. While they also aim for financial returns, their defining feature is the assessment of environmental impact and social responsibility of the investments are assessed using key indicators such as carbon emissions, energy efficiency, and social conditions.

By applying sustainability criteria (such as environmental, social, and governance—ESG criteria), these funds allow investors to make informed decisions that not only lead to economic benefits but also support socially and environmentally responsible initiatives. In this context, green investments have the potential to create significant changes both at the corporate level and globally, encouraging companies to adhere to high standards of sustainable management and corporate responsibility.

Green funds encounter difficulties in maintaining transparency and accountability, particularly due to varying global standards and risks of greenwashing. Regulatory frameworks, such as the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), aim to address these issues but can impose compliance costs, especially for smaller funds[2]. The effectiveness of green funds depends on quality regulations and incentives that encourage not only investors but also organisations to actively participate in this process while ensuring real value for sustainable development.

The Berlaymont building, by night, illuminated in green for the European Green Deal, symbolizing the EU’s commitment to sustainable finance and climate neutrality.

Photographer: Lukasz Kobus

Architect: André Polak, Lucien De Vestel, Jean Gilson, Jean Polak

Source: European Union 2021

© European Union, 2025, CC BY 4.0

Green investments and funds are a response to global environmental and social issues and a crucial driver of long-term innovation and development. With the growing importance of ESG factors in financial markets, green funds are establishing themselves as an important element of financial strategy and also as a foundational part of global efforts for a sustainable future.

Historical Development of Regulations

The historical development of regulations related to green investments reflects the evolution of international and national policies in response to growing environmental and social challenges. Initial regulatory efforts for environmental finance began in the 1970s with the 1972 UN Stockholm Conference, which emphasized environmental protection and influenced national policies. More structured attempts emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, culminating in the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which established legally binding targets for reducing carbon emissions[3]. This document laid the foundations for financial mechanisms, such as the emissions trading system, which encouraged the private sector to invest in sustainable projects.

During this period, the first guidelines for reporting on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental impacts also emerged. These set the stage for the integration of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria into investment strategies.

In the first two decades of the 21st century, regulations related to green investments developed significantly. The European Union (EU) established itself as a global leader in this field, adopting several directives and regulations to promote sustainable finance. The EU Taxonomy Regulation, officially published on June 22, 2020, and effective from July 12, 2020, establishes a standardized framework for classifying environmentally sustainable economic activities, aligning with the European Green Deal[4].

At the same time, globally, the United Nations (UN) contributed to the development of green finance through initiatives such as the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) introduced in 2006, and the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015.

Currently, regulations related to green investments cover a wide range of aspects, including transparency, sustainability reporting, and the management of climate-related risks. In 2021, the EU introduced the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which requires financial institutions to disclose how their investments contribute to sustainable development.

Additionally, central banks and financial regulators began integrating sustainability into their policies. For example, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), established in 2017, encourages central banks and regulators to develop strategies for addressing climate risks.

Regulatory Frameworks

The Role of Regulations in the Development of Green Investments

Green investment funds are increasingly influenced by regulatory frameworks aimed at promoting sustainability and transparency. Key European policies, such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy, form the foundation of these frameworks. They require financial institutions to disclose the environmental and social impacts of their investments, leading to significant changes in the operations of green investment funds. SFDR mandates the disclosure of sustainability-related risks at both organisational and product levels, improving transparency for investors and aligning with environmental goals. It is a key step towards increasing transparency and promoting sustainable investments within the financial sector. Entering into force in March 2021, SFDR is part of the EU’s broader strategy to achieve the Green Deal goals and redirect capital flows towards sustainable economic activities. The regulation imposes disclosure requirements on sustainability at both the company and financial product levels, focusing on reducing information asymmetries between investors and financial institutions.

Key Requirements of SFDR

SFDR divides disclosure obligations into three main levels:

| SFDR Article | Description | Example Products |

| Article 6 | Products that do not aim to promote sustainability. | Traditional investment funds. |

| Article 8 | Products that promote environmental and/or social characteristics but do not have sustainability as their primary objective. | ESG funds targeting low-carbon emissions. |

| Article 9 | Products that have a clear sustainability objective as the primary investment goal. | Green bonds for renewable energy. |

SFDR promotes transparency in green funds by requiring them to demonstrate their contribution to sustainability through specific, verifiable indicators. This encourages effective data management on environmental and social impacts, making it easier for investors to make informed decisions.

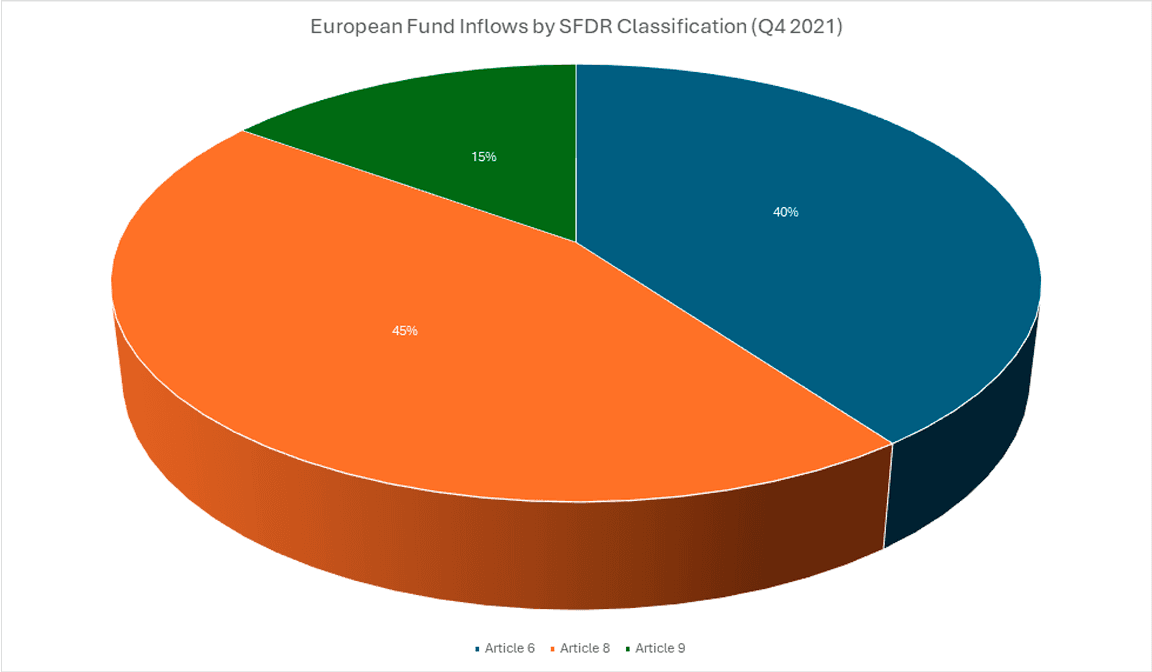

Studies suggest SFDR’s fund classification (Articles 6, 8, and 9) enhances investor ability to compare sustainable products, with Article 8 and 9 funds capturing over 60% of European fund inflows in Q4 2021. However, challenges like inconsistent interpretations and greenwashing risks persist, as noted by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA)[5].

Graph 2: SFDR Fund Inflows by Article (Q4 2021)

Source: ESMA (2023). Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG or sustainability-related terms.

Phases of SFDR Implementation

Timeline for Fund Transparency

| Date | Disclosure Phase | Requirements |

| March 2021 | Initial phase | Mandatory core sustainability disclosures at the product level. |

| January 2022 | Additional details | Expanded data on adverse impacts. |

| December 2023 | Compatibility with Taxonomy | All funds must declare alignment with environmental goals. |

Despite the positive effects of SFDR, there are significant challenges and criticisms regarding its implementation:

The SFDR regulation is expected to be further refined through alignment with other EU initiatives, such as the Taxonomy and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). The creation of unified standards and metrics for assessing sustainability will be key to the future effectiveness of the regulatory framework.

The European Taxonomy

The European Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (EU Taxonomy) is a key element in the European Union’s efforts to promote sustainable development and the transformation of the economy towards more sustainable and climate-neutral models. It represents a system of criteria that define which economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable, with the aim of encouraging investment in activities that have climate-beneficial outcomes. The Taxonomy is part of the EU’s broader strategy to achieve climate goals within the European Green Deal and transition to a carbon-neutral economy by 2050[7].

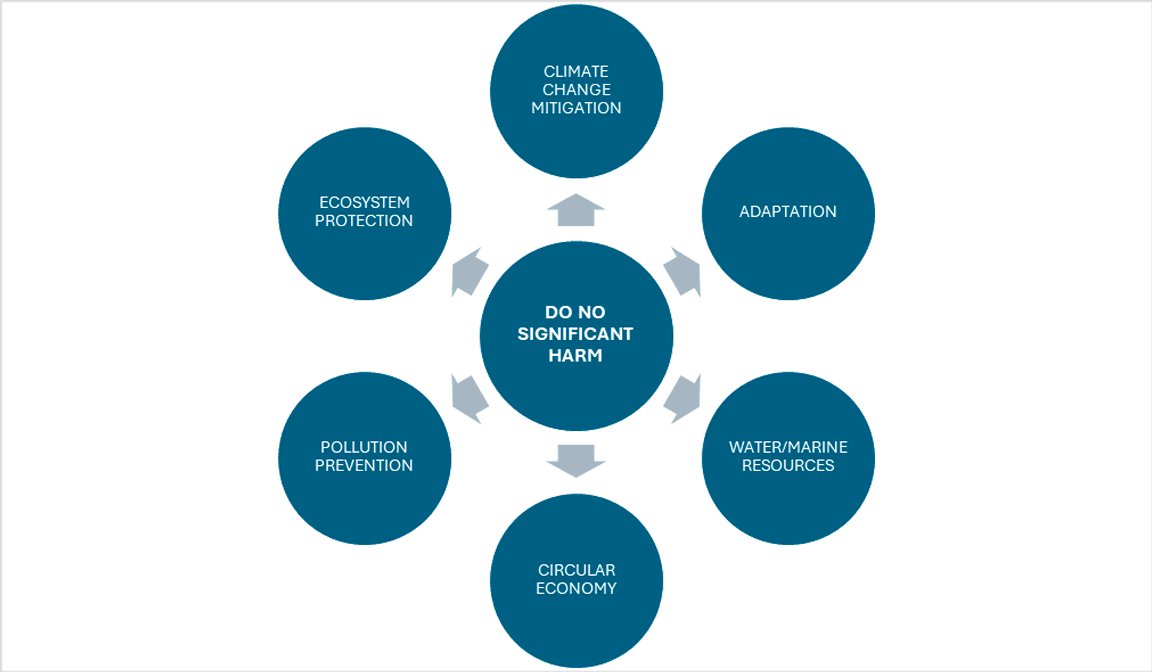

EU Taxonomy Framework Diagram

Source: European Commission (2020).

Adopted in 2020, the Taxonomy consists of a set of criteria covering six key environmental objectives: (1) climate change mitigation, (2) climate change adaptation, (3) sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, (4) transition to a circular economy, (5) pollution prevention, and (6) protection of ecosystems. The EU Taxonomy classifies renewable energy production, such as wind power, as sustainable if lifecycle emissions are below 100 gCO2e/kWh, ensuring only low-carbon activities qualify[8]. The goal is to facilitate the transition to sustainable investments by providing a reliable and sound basis for assessing the sustainability of specific projects and activities.

The main principles of the Taxonomy include requirements for activities to not only contribute to the achievement of environmental goals but also to not cause significant harm to any of these objectives (the “do no significant harm” – DNSH principle). This is an important mechanism to ensure that investments considered sustainable truly have a positive impact on the environment and do not lead to significant harm to nature or to the social and economic conditions in the relevant regions.

The EU Taxonomy offers clear, measurable criteria for identifying sustainable projects, such as specific carbon emission thresholds for renewable energy. However, its complexity, particularly for SMEs, has raised concerns about compliance costs and accessibility, as noted by the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC)[9].

The Taxonomy also encourages financial institutions and investors to focus on projects that comply with these standards by providing them with a clear framework for assessing sustainability. For financial products and investments presented as sustainable, the Taxonomy’s requirements are mandatory, and they must disclose how their investments align with environmental criteria. This is crucial to achieving the EU’s goals for reducing carbon emissions and achieving climate neutrality by 2050, as increasing investments in sustainable activities is a core part of the strategy for transitioning to a green economy.

The Taxonomy provides clear and measurable criteria that help investors identify and support sustainable projects. At the same time, it establishes a foundation for reliable and consistent standards that can be applied across different sectors of the economy, including the energy, transport, agriculture, and other sectors. To meet the Taxonomy’s requirements, companies must publish detailed information about their activities, which will also increase corporate transparency and allow investors to make informed investment decisions.

Thus, the EU creates a regulatory framework that not only stimulates investment in sustainable activities but also provides the necessary foundation for the development of green financial instruments and policies. In this way, the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance plays a central role in the transition to sustainable economic development and in achieving the EU’s climate goals.

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and its Upgrade with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) was introduced by the European Union in 2014 to provide better transparency regarding the environmental, social, and governance aspects of companies’ activities. Under this directive, large public companies are required to disclose information about their policies and risks related to sustainability, allowing stakeholders, including investors, to assess the impact of these companies on society and the environment. The goal was to address the need for more in-depth and detailed corporate reporting, providing data that is essential for long-term financial analysis[10].

Despite the successful implementation of the NFRD, the increasing demand for more standardized and widely applicable sustainability reporting led to the development of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), proposed by the European Commission in 2021. The CSRD expands the scope of the NFRD by including more companies, such as small and medium-sized publicly registered enterprises. The changes in legislation aim to create a level playing field for all companies, making the reporting of environmental and social indicators mandatory for a significantly larger number of organisations[11].

In addition to the expanded scope, the CSRD also integrates the requirements of the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. This means that companies must disclose how their activities contribute to achieving the environmental goals set by the EU. This added value of the CSRD is crucial for the integration of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) factors into investment strategies and allows investors to assess corporate sustainability based on clear and measurable standards[12].

In parallel, the global uptake of ISSB standards (IFRS S1 and S2) is creating convergence opportunities with EU reporting frameworks, helping multinational companies align disclosures globally.

The CSRD standardizes reporting through the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which align with international frameworks like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), ensuring globally comparable sustainability data[13]. This alignment with global standards is important for facilitating internationally consistent and comparable sustainability information to meet the growing demands of markets for sustainable investments. It is important to note that the CSRD strengthens corporate accountability while creating better awareness among investors, which is key to the transition towards more sustainable investment practices within the EU.

The goal of the CSRD is to provide better information about both the financial and non-financial performance of companies, allowing investors to make informed decisions based on fully integrated data on sustainability-related risks and opportunities. As part of the European Green Deal, the CSRD aims to deepen the EU’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions and achieve climate goals, ensuring long-term benefits not only for investors but also for society as a whole.

As of 2025, large companies are submitting their first sustainability reports under the CSRD for the 2024 financial year. SMEs listed on public markets will comply gradually, with full implementation by 2026, allowing preparation time for smaller entities[14].

Impact of Regulations on Green Funds

Green investment funds are not only catalysts for the transition to sustainable development but also play a central role in reducing carbon emissions and stimulating innovations in green technologies. Despite their crucial role in transitioning to low-carbon economies, the success of these funds is not solely driven by market mechanisms but is also significantly influenced by regulatory incentives and government support.

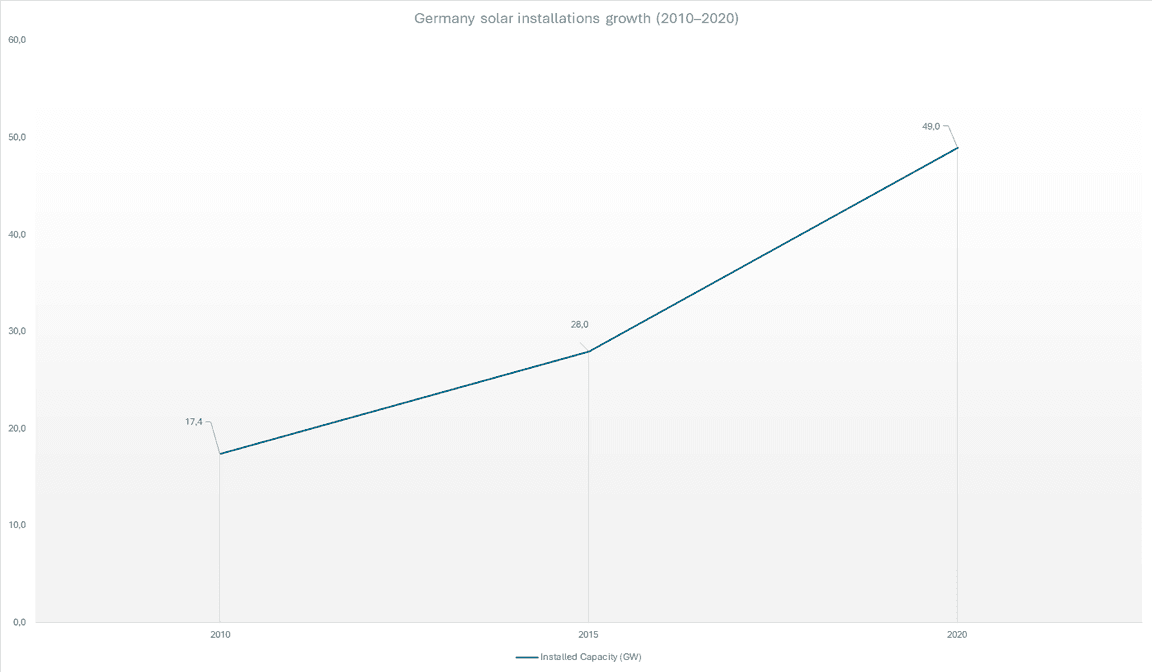

Regulatory incentives, such as tax breaks and subsidies, have driven innovations in sustainable financing. For instance, Germany’s feed-in tariffs for solar energy under the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) increased solar installations by 60% from 2010 to 2020, fostering green technology development. Similarly, the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme provided €80 billion for sustainable innovation[15]. Examples include accelerated depreciation applied to investments in green technologies, as well as various financial incentives that reduce the financial burden on companies investing in sustainable projects.

Graph 4: Germany Solar Installations Growth (2010–2020)

Source: German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (2020). Renewable Energy Sources Act.

Just Transition Mechanisms and Social Effects

The European Just Transition Mechanism, part of the European Green Deal, allocates €55 billion (2021–2027) to support regions dependent on high-carbon industries, such as coal mining in Poland’s Silesia region, by funding retraining programmes and green infrastructure to mitigate social and economic costs[16]. These programmes aim to ensure job sustainability and prepare regions for more eco-friendly industries, thereby reducing the social costs of the transition.

Although regulatory measures provide substantial advantages, they also present significant challenges for funds. Increased accountability requirements, including those related to determining the ecological impact of projects, may lead to additional compliance costs. However, these regulations are necessary to ensure transparency and prevent issues like greenwashing, which would undermine confidence in green investments.

Regulatory Approaches to Green Investments in Different Jurisdictions

When examining the application of regulations for green investments across different jurisdictions, it is clear that, while there are common themes, the approaches vary significantly between regions such as the European Union (EU), the United States (US), and Asia. Each of these areas has developed regulatory frameworks aimed at guiding and stimulating green investments, but the scope, strictness, and enforcement mechanisms differ.

When examining the application of regulations for green investments across different jurisdictions, it is clear that, while there are common themes, the approaches vary significantly between regions such as the European Union (EU), the United States (US), and Asia. Each of these areas has developed regulatory frameworks aimed at guiding and stimulating green investments, but the scope, strictness, and enforcement mechanisms differ.

European Union (EU)

The EU is a leader in shaping sustainable finance, primarily through its EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). The EU’s regulatory framework is highly structured and includes detailed technical criteria to determine which investments are considered sustainable. The EU Taxonomy classifies renewable energy production, such as wind power, as sustainable if lifecycle emissions are below 100 gCO2e/kWh, ensuring only low-carbon activities qualify[17]. This type of regulatory oversight ensures that funds claiming to be “green” adhere to a common set of standards, enhancing market trust and directing capital to environmentally sustainable projects. Furthermore, the EU Green Bond Standard (GBS) promotes transparency in green financing.

United States (US)

In contrast, the US does not have a unified regulatory framework for sustainable finance akin to the EU’s taxonomy. Although there is a growing trend towards sustainable investments, regulation is more fragmented and often focuses on market-driven solutions rather than mandatory disclosures. In March 2022, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed rules mandating climate risk disclosures, including Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions for public companies. As of May 2025, these rules remain under review due to legal challenges, with partial implementation expected in 2026[18]. Without a standardized US framework, investors rely on global voluntary standards like the Climate Bonds Initiative and Green Bond Principles, which certify green bonds for projects like renewable energy. For example, Apple issued $4.7 billion in green bonds certified under these standards in 2021[19]. Additionally, tax incentives and subsidies, such as the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) and Production Tax Credit (PTC), are crucial mechanisms supporting green investments in the US. While these tax credits play an essential role in promoting clean energy, the regulatory landscape remains more fragmented compared to Europe.

The official logo of the Climate Bonds Initiative, representing global standards for green bond certification.

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative (2021).

Asia

Asia presents a diverse range of approaches to regulation due to differences in political, economic, and environmental contexts across countries. Nations like China and Japan have introduced significant regulations for green financing, but their frameworks tend to prioritise economic growth via green investments over strict enforcement of environmental standards.

In China, the Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue, revised in April 2021 by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), defines eligible green bond projects and explicitly excludes fossil fuel-related activities to better align with international sustainability standards[20]. This update marked a significant step toward harmonizing China’s green finance framework with global norms.

According to the PBoC and the Climate Bonds Initiative, China issued approximately USD 130 billion in green bonds in 2023, making it one of the largest green bond markets globally[21]. The Catalogue continues to serve as the foundation for determining the eligibility of green projects and is reinforced by China’s Green Finance Guidelines, which now increasingly emphasize environmental impact assessment and disclosure requirements[22].

Despite this growth, transparency and reporting quality in China’s green bond market remain areas for improvement when compared to the EU Taxonomy framework, which enforces stricter “Do No Significant Harm” (DNSH) and reporting obligations[23]. However, ongoing policy enhancements—including joint efforts by the PBoC, China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), and National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC)—are gradually closing this gap by requiring more detailed environmental disclosures and third-party verification[24].

In Japan, the Green Growth Strategy (2020) and financial institutions like the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), which issued $2.5 billion in green bonds in 2022, promote green investments. Tax incentives for renewable energy further support the transition[25]. The country also offers subsidies for renewable energy, which play an important role in the transition to a low-carbon economy. However, as in China, the regulatory frameworks in both China and Japan do not exhibit the same level of transparency and detail as those in the EU.

Examples of Successful Green Funds

The effectiveness of these regulatory frameworks can be illustrated through examples of successful green funds operating in these regions.

In the EU, the Amundi Planet Emerging Green One Fund, managed by Amundi, is a leading green bond fund, with $1.5 billion in assets under management as of 2023, benefiting from EU Taxonomy alignment and investor trust in regulatory clarity[26]. The fund primarily invests in projects that align with the EU’s climate and environmental goals, offering a clear example of how regulatory clarity can lead to successful green investments.

In the US, the Calvert Green Bond Fund, managed by Calvert Research and Management, invests in sustainable projects and operates in a less regulated environment, relying on voluntary standards like the Green Bond Principles. It managed $800 million in assets as of 2023[27]. Its success is based on the growing demand for sustainable investments, supported by voluntary standards rather than mandatory government regulations.

In China, the green bond market has grown significantly in recent years, with government activity in green financing supporting investments in clean energy and environmental protection. The success of Chinese green bonds has been bolstered by regulatory approval for green projects and tax incentives, but challenges remain in standardizing disclosures and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Upcoming Changes in Regulations – New ESG Reporting Requirements

One of the key areas of upcoming regulatory changes is the increased demand for ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) reporting. Regulators around the world, including the European Commission and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), are planning significant expansions of corporate reporting obligations related to environmental, social, and governance factors. The SFDR, effective since March 2021, continues to evolve with enhanced requirements, while the CSRD, effective for large companies’ 2024 financial year (reporting in 2025), mandates detailed ESG disclosures to demonstrate contributions to a climate-neutral economy[28].

Digital solutions, including AI-driven platforms, are increasingly used by funds to manage ESG disclosures and ensure compliance with SFDR and CSRD in real time.

These new regulations will impose stricter reporting requirements on businesses, demanding detailed ESG disclosures at the corporate level, including specific and verifiable metrics. It is expected that this will lead to greater transparency and improved management of environmental and social risks, having a significant impact on markets by encouraging investors to focus on sustainable business practices.

Additionally, the new ESG reporting requirements will extend to investment funds, which will be obligated to disclose their compliance with sustainability standards and demonstrate how their investments align with the EU’s sustainable development goals. Furthermore, financing green initiatives will increasingly be subject to precise standards and regulated criteria, ensuring that green bonds and funds meet sustainability requirements.

Transition to Mandatory Regulatory Frameworks for All Investment Funds

Another important trend is the move toward mandatory regulatory frameworks for all investment funds. This will mean that all financial products claiming to be “green” must meet uniform standards, regardless of the jurisdiction in which they operate. In the EU, this process will be accelerated through the implementation of the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance, which imposes strict requirements on investors and funds regarding how and where their capital flows will be directed to meet environmental and social goals.

Jurisdictions like the US and Asia are developing sustainable finance regulations, but alignment with the EU’s approach remains uncertain. The SEC’s proposed climate disclosure rules (2022) and Asia’s taxonomies (e.g., Singapore’s taxonomy) indicate progress, but priorities differ due to local contexts[29]. With the growing global integration of capital markets, efforts to create unified regulatory frameworks will help reduce legal and operational uncertainties related to green financing, making investments in green funds more attractive and easier to follow.

This transitional phase will also require innovations in green bonds and other financial instruments, which will be regulated under new, stricter standards. Full implementation of the EU taxonomy and similar initiatives will provide clear guidelines for which projects can be classified as green and how their effectiveness will be measured.

European Commission Omnibus Simplification Package[30]

On 26 February 2025, the European Commission adopted a simplification package. It covers a number of legislative areas, including sustainable finance rules, carbon border adjustment mechanism and investment with the aim of simplifying EU rules, enhancing competitiveness and attracting investment. This initiative is part of the Commission’s commitment to reduce administrative burdens by 25% for all businesses and 35% for SMEs.

In order to boost competitiveness and unleash growth, the EU needs to foster a favourable business environment and ensure that companies are not stifled by an excessive regulatory burden. This, in turn, will unlock investments and enable companies to embrace the transition to a sustainable economy in a more effective and pragmatic way, ultimately meeting EU climate and other sustainability goals. The “Omnibus” package will reduce compliance complexities for all companies, while focusing the rules on the largest companies that have a bigger impact on the environment and climate.

The sustainability “Omnibus” includes amendments to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), accompanied by a draft Taxonomy Delegated Act for public consultation, with the aim of making sustainability reporting more efficient and less burdensome. The main changes in the area of sustainability reporting will:

A separate “stop the clock” proposal will also postpone by two years the reporting requirements for companies currently in the scope of CSRD which were scheduled to report as of 2026 or 2027. This is to give time to the co‑legislators to agree to the Commission’s proposed substantive changes.

The proposed changes to the CSRD scope and future modifications to the ESRS could reduce administrative costs by approximately €4.4 billion annually. Immediate financial relief is anticipated, with one‑off savings for exempted firms projected at around €1.6 billion for Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) / European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) and €0.9 billion concerning taxonomy‑related requirements.

Conclusion

Regulatory changes, particularly in the EU with SFDR and CSRD, enhance accountability in sustainable finance by mandating transparent ESG disclosures. Globally, progress varies, with Asia’s taxonomies and US proposals advancing but not yet matching EU rigor[31]. The expectation is that future regulatory changes will lead to greater transparency and accountability, thereby boosting investor confidence in sustainable funds and providing clearer guidance on effectively channeling capital into sustainable and green projects. These efforts will require global cooperation and coordination between various jurisdictions, presenting a key challenge for future regulatory frameworks in this area.

In conclusion, sustainable financing and green investments represent both a strategic necessity for transitioning to a globally cleaner economy and an opportunity to create significant socio-economic benefits. With the growing importance of sustainable development, regulatory incentives, subsidies, and innovations in green technologies are crucial for addressing the global challenges related to climate change. However, the successful development of these tools is not only a result of market mechanisms but also of the complexity of the interaction between public policies and the private sector. In the future, achieving sustainable outcomes will require global collaboration to harmonize regulatory frameworks and actively promote innovation in financial technologies. Only through the joint effort of governments, corporations, and civil organisations will an effective and sustainable economic system be created, ensuring long-term economic growth without compromising the planet’s natural resources.

[1] Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2020). Global Sustainable Investment Review.

[2] European Commission (2021). Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation.

[3] United Nations (1972). Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.

[4] European Commission (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment.

[5] ESMA (2023). Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG or sustainability-related terms.

[6] European Commission (2021). Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

[7] European Commission (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/852.

[8] European Commission (2021). EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act.

[9] EESC (2021). Opinion on Sustainable Finance Taxonomy.

[10] European Commission (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU.

[11] European Commission (2021). Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

[12] European Commission (2021). CSRD.

[13] European Commission (2021). European Sustainability Reporting Standards.

[14] European Commission (2021). CSRD

[15] German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (2020). Renewable Energy Sources Act; European Commission (2020). Horizon 2020 Programme.

[16] European Commission (2023). Just Transition Mechanism.

[17] European Commission (2021). EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act.

[18] SEC (2022). Proposed Rule on Climate-Related Disclosures.

[19] Climate Bonds Initiative (2021). Green Bond Market Report; Apple Inc. (2021). Environmental Progress Report.

[20] People’s Bank of China (2021). Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue (2021 Edition).

[21] Climate Bonds Initiative (2024). China Green Bond Market Report 2023.

[22] People’s Bank of China & China Securities Regulatory Commission (2023). Green Finance Guidelines & Disclosure Standards.

[23] European Commission (2020–2024). EU Taxonomy Regulation Documentation.

[24] Bloomberg & Refinitiv (2024). Green Finance Market Analysis – China, and CCDC (2023). Annual Green Bond Reports.

[25] Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan (2020). Green Growth Strategy; JBIC (2022). Annual Report.

[26] Amundi (2023). Fund Performance Report.

[27] Calvert Research and Management (2023). Fund Overview.

[28] European Commission (2021). SFDR and CSRD.

[29] SEC (2022). Proposed Rule on Climate-Related Disclosures; IEEFA (2024). Sustainable Finance in Asia.

[30] https://finance.ec.europa.eu/news/omnibus-package-2025-04-01_en

[31] European Commission (2021). SFDR and CSRD; IEEFA (2024). Sustainable Finance in Asia.

EU directive expanding the scope of non-financial reporting to more companies.

Guidelines from the European Securities and Markets Authority on the use of ESG-related terms in fund names.

Official EU regulation detailing sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector.

EU regulation establishing criteria for environmentally sustainable economic activities.