Introduction: Why the Next Seven Years Matter More Than Ever

On 16 July 2025 the European Commission published the first legislative draft of the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2028-2034—the EU’s seven-year budget blueprint. From coal-belt Silesia to the tech clusters around Cluj-Napoca, the choices made in Brussels over the next 18 months will determine whether Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) catches up, stands still, or falls behind in the twin green-digital transition, whether its eastern borderlands receive concrete for bunkers or fibre-optic cables for start-ups, and whether farmers from Debrecen to Dobrich can still rely on the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) cheques that have stabilised rural incomes since 2004.

The draft MFF 2028–2034 introduces a three-pillar structure that reshapes how funding is channelled and priorities are set. The table below summarises the main features, including indicative shares, what existing instruments will be replaced, and the relevance for Central and Eastern Europe.

Pillar | Share of budget (indicative) | What disappears | What replaces it | CEE relevance |

Pillar 1: National & Regional Partnership Fund (NRP) | ≈ 70 % | Traditional Cohesion Policy envelopes + CAP direct payments | country-specific “National & Regional Partnership Fund (NRP) contracts” | Cohesion funds for poorer regions folded into national envelopes |

Pillar 2: European Competitiveness Fund (ECF) | ≈ 15 % | 14 smaller programmes (Digital Europe, Defence Fund, parts of CEF, InvestEU, EU4Health, Space) | Single mega-fund for innovation, defence-tech, clean-tech and biotech | CEE universities & start-ups must now compete EU-wide for scale-up grants |

Pillar 3: Revamped External Action | ≈ 10 % | NDICI–Global Europe, IPA, humanitarian aid | Streamlined “Team Europe” instrument, heavier on Ukraine, migration, border hardening | Front-line states (PL, SK, HU, RO) could draw on border-security windows |

Table 1: EU Budget 2028–2034: The Three Pillars

The remaining ~5 % covers administration and the repayment of NextGenerationEU debt, which starts in 2028 and will cost €25–30 bn per year—roughly the size of the entire 2021-2027 cohesion envelope for Poland[1].

2.1 Cohesion Policy: From Regions to Capitals

For two decades, EU Cohesion Policy has channelled over €213 billion into Central and Eastern European (CEE) regions, helping lift GDP per capita from 45 % of the EU average in 2004 to 72 % in 2023. These transfers have underpinned roads in Podkarpackie, incubators in Plovdiv, and broadband in Banská Bystrica.

Now, the European Commission proposes a fundamental shift: scrapping individual regional envelopes and placing the majority of cohesion funding into national plans negotiated directly between Brussels and each member state’s finance ministry.

Winners vs. losers:

Fourteen CEE countries, led by Poland and Romania, have already circulated a non-paper rejecting the RRF model for the long-term budget, insisting on “a distinct and robust Cohesion Policy with region-based allocation”[2].

2.2 CAP: The Ukrainian Question

Ukraine’s potential accession would add 41 m ha of arable land—more than Germany and France combined—and €11 bn a year in CAP claims . The Commission’s proposal allocates €294 bn to CAP for 2028-34, a 20 % nominal cut compared with 2021-27. The three options left for financing Ukraine are:

Either option would reduce real transfers to CEE farmers, who rely on CAP for 20–40 % of farm income. At the same time, CEE agrifood exporters fear cheap Ukrainian grain depressing prices inside the Single Market. Romania, Bulgaria and Poland have already asked for “safeguard clauses” to limit Ukrainian imports if CAP compensation falls.

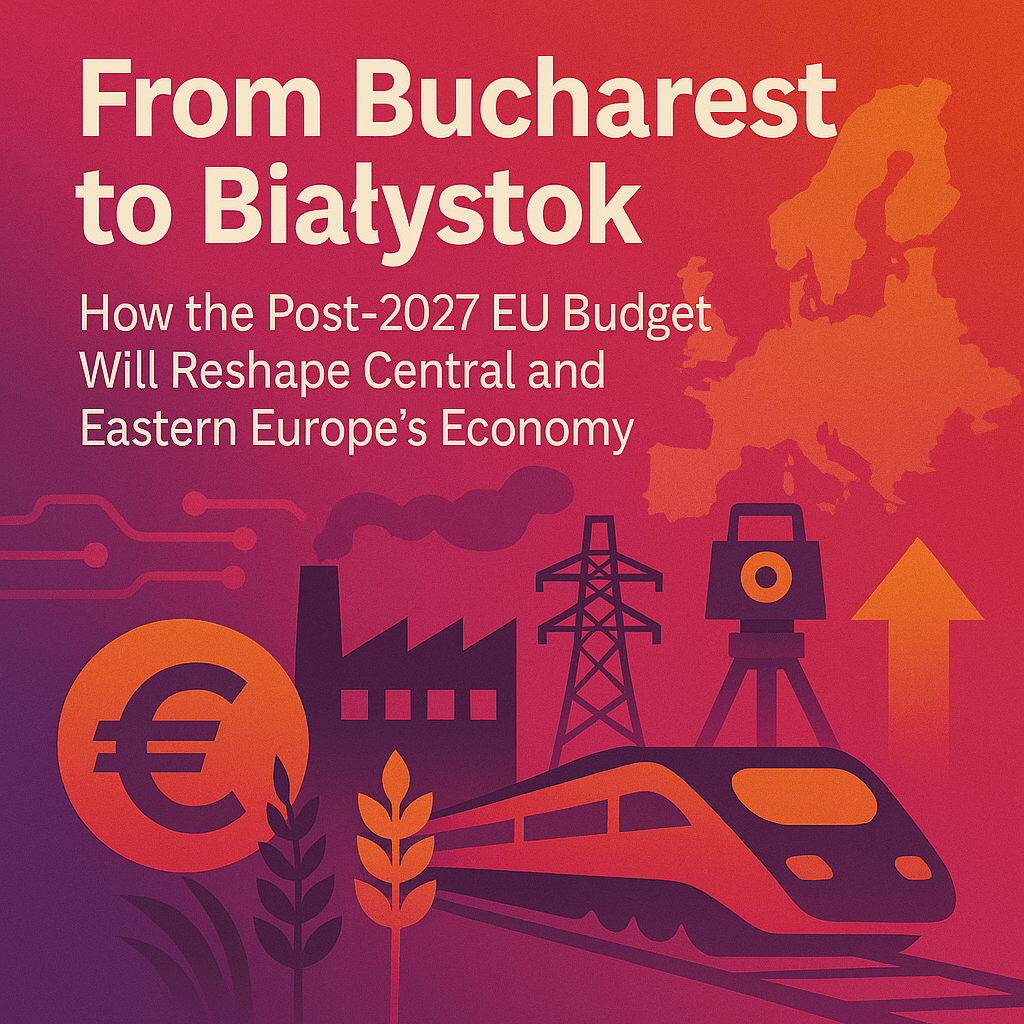

2.3 Defence and Border Infrastructure: A New Growth Engine?

Figure 1: Emerging Growth Zones Along the EU’s Eastern Frontier

Map highlighting CEE regions within 100 km of the EU’s eastern border, which could benefit from the proposed €100 bn ‘Security & Defence’ envelope under the European Competitiveness Fund (ECF) 2028–2034. Priority areas include Podkarpackie (PL), Satu Mare (RO), and southern Slovakia, targeted for dual-use infrastructure and defence-related investment.

What’s new?

Dual-use infrastructure—such as ports, railway spurs, 5G corridors, drone manufacturing zones—will become eligible for EU co-financing.

Funding will prioritise locations within 100 km of the EU’s eastern border, directly benefitting frontline states like:

CEE economic implications:

If successful, regions like Podkarpackie (PL) or Satu Mare (RO) could witness a mini-boom in defence-adjacent manufacturing, echoing the automotive and electronics boom that Western Slovakia experienced between 2010–2020. This could include:

EU Strategic opportunity: CEE governments are now lobbying the Commission to include location-based eligibility criteria in the final programme design, ensuring these investments support both NATO defence needs and regional economic development.

2.4 Repayment Shock and Net-Benefit Arithmetic

Starting in 2028 the EU must repay €25–30 bn a year of NGEU debt. Unless New Own Resources (CBAM, digital levy, FTT) are agreed unanimously, existing programmes will be squeezed.

CEE implications:

Country | Annual cohesion receipts (2021-27) | Share of NGEU repayment (indicative) | Net squeeze 2028-34 |

Poland | €16.0 bn | €4.2 bn | -26 % |

Romania | €7.5 bn | €1.6 bn | -21 % |

Hungary | €6.7 bn | €1.2 bn | -18 % |

Czechia | €3.8 bn | €1.0 bn | -26 % |

Table 2: Indicative Budget Squeeze from NGEU Repayments in CEE (2028–2034)

If Ukraine joins in 2031, Bruegel modelling indicates an extra €32 bn cohesion demand, pushing the real-term reduction for Poland to ‑33 % and Romania to ‑28 %.

Unless new revenues appear, every €1 of NGEU repayment crowds out €1 of cohesion money.

2.5 Talent and Social Transfers

The Commission wants to fold Erasmus+ and the European Social Fund+ into national envelopes. Although the final budget is still unknown, the Commission’s 17 July text keeps Erasmus+ as a standalone programme. CEE universities remain concerned about the envelope size, but the existential risk has been averted. Currently, Poland and Romania rank 1st and 3rd in Erasmus+ student numbers; a budget squeeze could reverse brain-drain gains made since 2014.

3.1 Automotive: From ICE Valleys to Battery Valleys

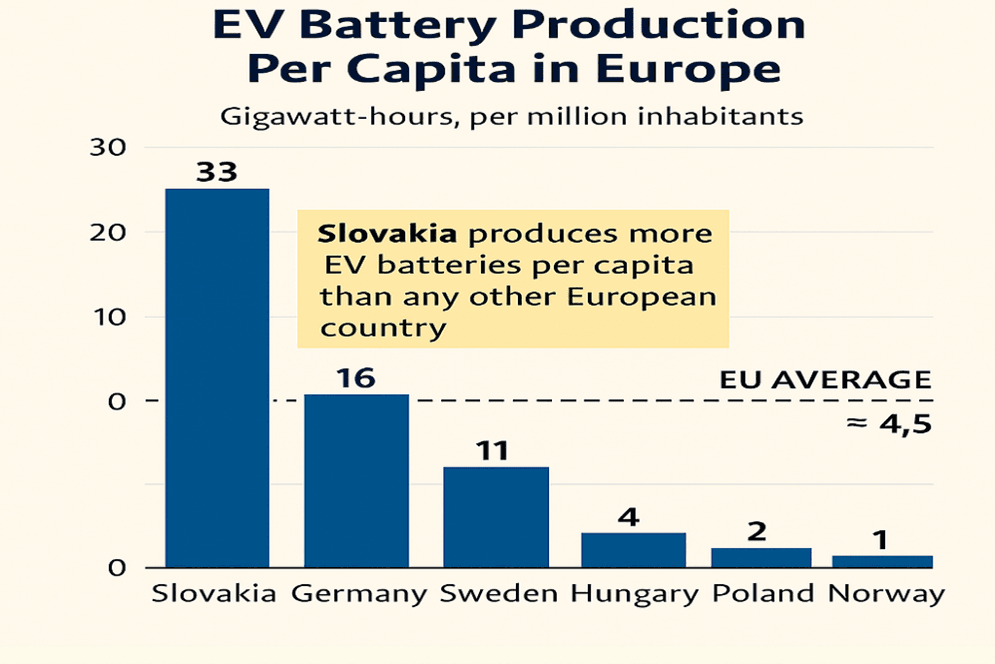

CEE has attracted €60 bn in EV-battery and e-motor investments since 2019, much of it drawn by cohesion co-financing (up to 40 % of large projects). The ECF’s Clean-Tech window will shift from grant-based to loan-&-equity instruments. Slovakia’s InoBat and Poland’s LG Energy Solution can probably raise private capital; Romanian start-ups without balance-sheet depth risk being priced out. Slovakia now produces more EV batteries per capita than Germany, largely thanks to generous co-financing under the 2021–27 MFF.

Figure 2: The Rise of Battery Valleys in Central and Eastern Europe

3.2 Energy: Nuclear vs. Renewables

CEE states want nuclear recognised as “strategic” under the ECF; the Commission’s draft currently limits “clean-tech” to renewables and grids. Czechia and Hungary could lose €1–2 bn in potential co-financing for small-modular reactors if the definition is not widened. Unless nuclear is explicitly included in the ECF taxonomy, Czechia’s Dukovany II and Hungary’s Paks III could struggle to meet EU sustainability criteria for financing.

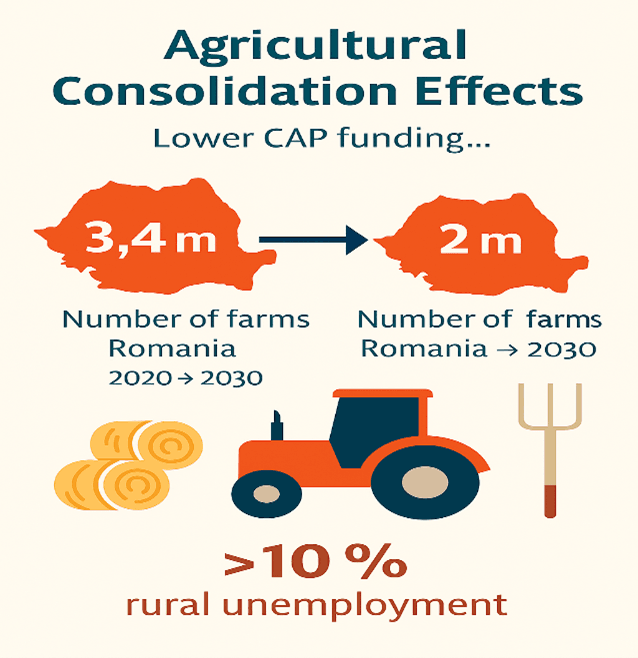

3.3 Agriculture: Consolidation Accelerates

Lower CAP envelopes will accelerate consolidation into 1 000+ ha holdings. In Romania, the number of farms could fall below 2 m by 2030 (from 3.4 m in 2020), pushing rural unemployment above 10 % in the poorest counties. Expect political push-back—farmer protests in Poland and Romania have already led to temporary import bans on Ukrainian grain. In Bulgaria, over 80 % of farms cultivate under 5 ha, making them highly vulnerable to direct payment cuts.

Figure 3: From 3.4 Million to 2 Million: Romania’s Farm Transformation

4.1 Sub-Carpathian Romania (NUTS-2 RO221)

4.2 Podkarpackie, Poland (PL323)

4.3 Northern Great Plain, Hungary (HU321)

5.1 Build a Blocking Minority on Cohesion

CEE + cohesion-friendly Southern states (e.g. Greece, Portugal, Spain) can form a blocking minority in the Council by surpassing the 35% population threshold. This would allow them to prevent reforms that undermine the current structure of Cohesion Policy.

Red line: maintain regional envelopes and retain a distinct legal basis for Cohesion, separate from performance-based national plans.

Regional allocation ensures that EU money reaches the poorest NUTS-2 regions—not just capital cities. Scrapping these envelopes would centralise decision-making and risk political capture by dominant governments.

In the 2013 MFF negotiations, a coalition led by Poland, Hungary, Portugal and Greece successfully pushed back against centralisation attempts, preserving regional allocation logic. A similar coalition, revitalised in 2025–2026, can use the same leverage.

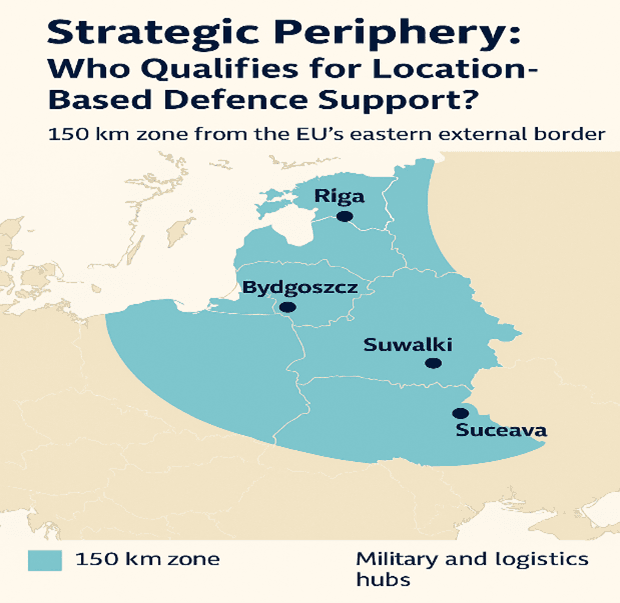

5.2 Push for Location-Based Defence Criteria

CEE countries should formally lobby for at least 30% of the ECF Security & Defence window to be earmarked for projects located within 150 km of the EU’s eastern external border—a zone that includes Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary and the Baltic States. This should be justified through NATO’s forward-defence doctrine, which prioritises rapid infrastructure readiness near frontline areas.

Figure 4: Defence Investment Eligibility by Location

Policy rationale:

Precedent and feasibility:

Strategic benefit for CEE:

Suggested action points:

5.3 Trade CAP Cuts for Market Access

Accept gradual CAP reductions in return for a permanent safeguard clause on Ukrainian agri-food imports and dedicated export-credit guarantees for CEE food processors. This approach would mirror existing EU trade arrangements with countries like Morocco and Tunisia, where preferential market access is balanced with quantitative import limits and sectoral safeguards.

To mitigate potential price shocks and income losses for small and medium-sized CEE farmers, governments should push for a transitional adjustment facility, funded either through the EAGF or EAFRD, to support value-chain upgrades and diversification efforts.

Additionally, permanent mechanisms for monitoring import volumes and triggering automatic tariff reintroduction in case of market disruption—similar to the “automatic stabilisers” in trade deals—should be embedded into the Ukraine-EU trade framework from 2028 onward. This would ensure a predictable investment environment for agri-food players in Eastern Europe, even as CAP envelopes decline.

5.4 Create a CEE “Just Transition Club”

Pool technical assistance funds from Czechia, Poland, Romania and Slovakia to design cross-border, bankable projects—such as carbon capture and storage (CCUS), green hydrogen corridors, and small modular reactors (SMRs)—eligible for financing under the ECF’s loan and equity windows. This would help bridge the expected grant shortfall in the 2028–2034 period and ensure CEE access to capital-intensive transition technologies.

The club could be modelled after successful instruments like the Baltic Innovation Fund or the Three Seas Investment Fund, with co-investment from national development banks and advisory support from the European Investment Bank (EIB). By acting collectively, CEE countries would also gain stronger negotiation leverage vis-à-vis EU institutions in shaping eligibility rules and technical scoring criteria.

Furthermore, the club could serve as a knowledge-sharing and project incubation platform—standardising feasibility assessments, pooling engineering capacity, and coordinating permitting processes for transnational infrastructure and clean-tech investments.

5.5 Ring-Fence Erasmus+ and ESF+

Central and Eastern European (CEE) governments should use the European Parliament’s May 2025 resolution as political leverage to demand that Erasmus+ and the European Social Fund+ (ESF+) retain their standalone legal bases in the post-2027 budget framework. Beyond their social value, these programmes play a strategic role in strengthening the competitiveness and resilience of the region.

Erasmus+ has helped reverse brain drain by embedding young talent within pan-European networks and enabling high-skilled return migration. In 2023 alone, over 150,000 students from Poland and Romania participated in Erasmus+, making them the top two beneficiaries. Cutting or merging these programmes into broader national envelopes would weaken their effectiveness and create long-term divergence within the EU’s knowledge economy.

CEE countries should frame Erasmus+ and ESF+ not as redistributive tools but as investments in future labour productivity, innovation ecosystems, and democratic cohesion—key dimensions of strategic competitiveness.

Date | Milestone | CEE Action Point |

16 Jul 2025 | Commission legislative package | Publish joint “CEE Competitiveness & Cohesion Pact” |

Sep 2025 | Second package (details, own resources) | Table amendments in Council Working Party |

Q1 2026 | Parliament adopts position | Secure rapporteurships for CEE MEPs on regional development file |

Q2-Q4 2026 | Trilogue negotiations | Activate regional assemblies (e.g., V4, Bucharest Nine) |

Dec 2026 | Target political agreement | Final red-line vote in Council |

2027 | Ratification & adoption | National parliaments must ratify own-resources decision |

Table 3: Key Milestones and CEE Leverage Points (2025–2027)

The post-2027 MFF is not merely a technical budget exercise; it is Europe’s first post-war, post-pandemic, post-enlargement financial constitution. For CEE the choice is stark:

History shows that CEE punches above its weight when it negotiates collectively (e.g., blocking the Services Directive in 2006, securing Just Transition Fund in 2020). The next 18 months will decide whether 2034 finds the region converged, secure and green—or resentful, under-funded and vulnerable to the next geopolitical shock.

[1] https://ecdpm.org/application/files/5317/3451/5922/The-multiannual-financial-framework-after-2027-Discussion-Paper-383-2024.pdf

[2] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2024/766224/IPOL_BRI(2024)766224_EN.pdf

Analysis of Ukraine’s evolving role as a low-cost defence producer influencing EU defence and reconstruction policies.

Analytical framing paper on post-2027 MFF negotiations, priorities, structure, and EU external action.

The EU’s MFF 2028–2034 is tailored to facilitate enlargement through reinforced external action and diplomatic engagement, but the budgetary costs and exact provisions remain contingent on final accession agreements and the broader financial pressures the EU faces.

The Commission’s proposal for the Multiannual Financial Framework 2028–2034, outlining budget priorities and new instruments.

Overview of the Just Transition Fund, launched as part of the European Green Deal to support regions in the low-carbon shift.