THE PROVISION IN QUESTION AS A PRELUDE

THE CONCEPTUAL ELEMENTS OF EXECUTION AS A SERVICE

1. Intermediation

2. Mifidisation?

2.1 Reasons pro Mifidisation

2.1.1 By reason of matter

2.1.2 By reason of entities involved

2.2 Reasons against Mifidisation

2.2.1 The non-mandatory intermediation

2.2.2 The concentration of functions

2.3 Conclusion

3. Agency

3.1 Execution as a form of agency in both legal and economic terms

3.2 Execution through or also with the CASP?

BEST EXECUTION AND OTHER REGULATORY ASPECTS OF THE CASP

SERVICE OF EXECUTION

1. Best execution

1.1 Best execution as a specific fiduciary duty

1.2 Abrogating specific client instructions

2. Order execution policy

2.1 Key aspects of the order execution policy

2.1.1 Execution policy and execution arrangements

2.1.2 Providing appropriate and clear information on the execution policy

and the meaning of ‘significant changes thereto’

2.1.3 Timing for obtaining prior consent to the order execution policy

2.1.4 Demonstrating agreed and compliant execution

2.2 About the content of the order execution policy

3. The concept of ‘execution venues’

Article 78

Execution of orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients

The conceptual elements of execution as a service

1. Intermediation

The CASP service of execution of orders forms part of the business model known as brokerage[1]. Its difference from the homonymous service in the financial instruments markets is that execution as a CASP service is provided in relation to crypto-assets falling under MiCAR and not financial instruments. Brokerage constitutes a form of financial intermediation[2]. In the case of brokerage, the intermediation mission performed resides in linking the buyer, of a crypto-asset in casu, to the seller and vice versa; this way, trades are concluded and, subsequently, liquidity is provided to the market, attributing to brokers the specific role of a market intermediary[3]. At the same time, the CASP service of execution is provided not only in respect of secondary market operations, in particular trading in crypto-exchanges; but also in respect of primary market ones, namely in the context of initial offerings[4]. However, a CASP providing the CASP service of execution is not to be perceived as a ‘neutral intermediary’ as is the case with the operator of a crowdfunding platform [5]; or as a ‘servant of two masters’ as is the case with an escrow agent[6], an intermediary known from cross-border transactions. The reason therefore being that a broker providing execution in crypto-assets or financial instruments is an intermediary on behalf of its client[7], hence owing a fiduciary duty towards the client only[8].

For MiCAR purposes the non-existence of intermediaries is tantamount to the concept of ‘decentralisation’ which describes those trading environments that are excluded from the scope of application of MiCAR[9]. Conversely, what is to be perceived as intermediation from a financial services perspective is to be understood as ‘centralisation’ from a regulatory perimeter perspective in the context of MiCAR.[10]

2. Mifidisation?

2.1 Reasons pro Mifidisation

2.1.1 By reason of matter

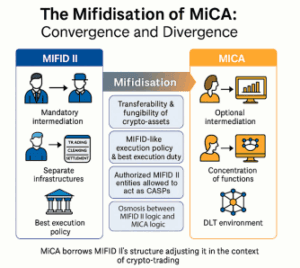

In the doctrine the term ‘Mifidisation’ has been used to describe the similarities between MiFID II and the regulation of CASPs under MiCAR, as the MiFID II regime is considered to stand as the clear reference model.[11]

The regulation of the CASP service of execution indeed seems to bear significant similarities with the homonymous MiFID II service, starting from the wording of Article 78 of MiCAR: There are MiFID II-like provisions for a best execution policy[12], abrogating client instructions[13], demonstration of compliance with the order execution policy[14] and the CASP’s possibility to execute transactions outside a trading platform, hence on another execution venue[15]. The latter is a term broader than the term trading platforms under MiCAR[16], as is such term broader than the term trading venues[17] under MiFIDII[18].

However, there are not only the said textual arguments[19] advocating for the significant influence of MiFID II and the subsequent application of the ‘prior instruction doctrine’[20] in the context of innovative technologies, such as DLT[21]. The impact of MiFID II in the said context is not only supported but, more than that, justified by nature of the crypto-assets falling under MiCAR’s scope, since a crypto-asset falling under MiCAR has to be:

a) Transferable, as it emanates from the MiCAR[22] definition of a crypto-asset. At the same time transferability implies negotiability, which is a key criterion for a transferable security, i.e. a financial instrument, within the meaning of MiFID II.[23] Thus, crypto-assets under MiCA display the characteristics of transferability, as do also transferable securities, which are financial instruments, under MiFID II; and

b) Fungible[24], same as transferable securities[25].

Thus, crypto-assets under MiCA are designed with the potential of a financial use, similarly to financial instruments under MiFID II.

2.1.2 By reason of entities involved

The aforementioned rationae materiae arguments emanating from the conceptual proximity between financial instruments under MiFID II on the one hand and crypto-assets under MiCAR on the other hand are not the only ones doctrinally supporting the argument of Mifidisation.

There are further arguments, rationae personae this time. These emanate from the nature of the entities that are providing financial services under pre-MiCAR sectoral rules and which will be allowed under MiCAR to also provide the CASP services corresponding to their sectoral authorisation, without being subject to authorisation under MiCAR[26]. More specifically, the said entities provide MiFID II services either as a result of possessing a MiFID II authorisation; or by having ‘topped-up’ their sectoral authorisation to also provide MiFID II services[27].

They will be allowed under MiCAR to provide the CASP services deemed equivalent to the MiFID II services currently provided by them by means of notifying such intention to the competent NCA; and without being required to obtain any additional CASP authorisation under MiCAR[28].

The reason therefore being that ‘MiCA provides that entities that already have a license to provide financial services and that already went through the authorisation process with the NCA of their home Member State (such as investment firms, credit institutions, etc.), do not need to go through the entire authorisation process again. MiCA indeed presumes that such entities are generally capable of providing crypto-asset services…In other words, MiCA is paying deference to the existing authorisation…’.[29]

This means that the common denominator of the various authorisations held by the entities laid down in Article 60 of MiCAR is the (additional, where applicable) provision of MiFID-II services. Thus, there is an osmosis pointing out towards Mifidisation not only at instrument, namely crypto-assets falling under MiCAR, but also at entity level as well.

What corroborates the solidity of the conclusion on the impact of existing TradFi regulation, MiFID II being the cornerstone[30] thereof in the EU, on crypto-asset service provision activities is that the same view is shared by international standard-setting bodies as well, namely IOSCO[31], the FSB[32] and the BIS[33].

2.2 Reasons against Mifidisation

2.2.1 The non-mandatory intermediation

While CASPs providing the CASP service of execution are intermediaries by default, the intermediation offered by them is not mandatory, as is practically the case with their MiFID II counterparts. More specifically, the appointment of intermediaries, executing brokers in casu, is, practically, a ‘must’ under MiFID II, in order for a trader to get access to the market[34].

Conversely, crypto-exchanges[35] allow traders, including retail ones[36], not to appoint a broker and have direct, i.e. disintermediated access. The said approach has also been ‘imported’ in the context of the trading of tokenised securities under the DLT PilotR[37].

Thus, not only does MiCAR deviate from MiFID II standards in this respect, but, more than that, MiFID II adopts MiCAR standards on non-mandatory intermediation in the context of the DLT PilotR.

2.2.2 The concentration of functions

When it comes to trading and settlement finality of financial instruments, EU financial services legislation follows the lifecycle of a transaction, i.e. trading, clearing and settlement: Until entry into force of DLT PilotR, which is an optional regime though, it required the presence of separate market intermediaries and market infrastructures for the performance of these activities, namely separate legal entities, for reasons of stability, security and competition.[38]

Conversely, MiCA trading platforms, within the meaning of multilateral trading systems, demonstrate a concentration of functions[39] offering brokerage, custody and even conditioned matched principal trading services, in addition to order matching[40].

Thus, once again MiCAR deviates from the MiFID II standards, as it allows the same entity to offer order matching, order execution as well as other services, as per the prevailing commercial reality prior to MiCAR’s[41] adoption.

2.3 Conclusion

It emanates from the aforesaid that there are reasons both for as well as against the Mifidisation of CASP services, the CASP service of execution in casu. However, there is a significant difference between those two categories of reasons.

More specifically, the tradability and fungibility of crypto-assets falling within MiCAR’s scope as well as the ability of the notifying entities[42] to offer CASP services corresponding to their TradFi activity[43] are inherent and indispensable components thereof: There can be no crypto-asset falling within MiCAR’s scope, if it is not transferable and fungible; and there can be no notifying entity to avail of Article 60 of MiCAR, if it is not a financial services entity offering the MiCAR-equivalent MiFID II services in the TradFi sector.

Conversely, the non-mandatory intermediation as well as the concentration of functions are merely commercial arrangements or policy decisions respectively, hence something external and subject to change. For these reasons, Mifidisation is to be perceived as a conceptual element of the CASP service of execution.

3. Agency

3.1 Execution as a form of agency in both legal and economic terms

The CASP service of execution applies in the context of both primary as well as secondary market operations, namely both in the context of ICOs[44] as well as that of secondary trading on a trading platform. Besides, execution as a service is not a mere interaction, as it is the case with the service of reception and transmission of orders (RTO)[45], but produces legal results, since the executing firm concludes a legally binding transaction[46] on behalf of the client.

It is in essence the same difference that exists between an agent on the one hand and a nuntius/messenger on the other hand, as known from general contract law[47]: The nuntius does not express its own will on another person’s behalf, but only conveys another person’s will[48]. This also means that, since the CASP providing execution is the client’s agent[49], as it is deducted from the term ‘on behalf’[50], it cannot be the client’s counterparty[51].

Given the aforesaid, brokerage by means of the CASP service of execution has to be distinguished from brokerage by means of the so-called matched principal trading (MPT)[52] business model. In case of MPT, the trading outcome is commercially/economically equivalent to execution, because of the MPT broker not being exposed to market risk[53], but legally:

A) The MPT broker is counterparty[54] acting as a principal in both legs of the transaction in question, namely interposing itself as buyer to the seller and seller to the buyer. Conversely, in the case of execution, the broker is clearly an agent on the side of one of the counterparties to the transaction; and

B) The neutralisation of market risk in the context of MPT takes place as a result of (back-to-back) hedging, hence being an external element occurring pursuant to a hedging transaction. Conversely, the elimination of such risk is an inherent element of the executing broker’s capacity as the client’s agent, since this risk is always borne by the client being the principal instructing the agent.

Thus, the CASP service of execution, unlike MPT, constitutes agency in both legal as well as in economic terms.

| Aspect | Execution as a CASP Service | Matched Principal Trading (MPT) |

| Legal role | Agent acting on behalf of the client | Principal acting as counterparty in both legs of the transaction |

| Economic risk | No market risk (borne by the client) | Market risk neutralised externally via hedging |

| Nature of activity | Intermediation; execution produces a legally binding transaction for the client | Trading; interposition between buyer and seller |

| MiCAR classification | CASP service of execution (agencybased) | Trading against proprietary capital (principal-based) |

3.2 Execution through or also with the CASP?

Given that the CASP service of execution refers to the so-called ‘dealing as an agent’ business model, the question arises whether it is possible for a CASP to execute a transaction on behalf of its clients where the CASP itself is also the counterparty to the client in the transaction in question.

In essence, the question resides in whether the CASP can execute a client order as an agent, and also conclude it by acting as the client’s counterparty, namely by also dealing as a principal; and whether this constitutes a MiCAR crypto-asset service or is out of scope of MiCAR.

In the affirmative, the further question arises whether the CASP service of execution would ‘mutate’ by means of absorption into a ‘dealing as a principal service’[55], because of the CASP in question being also the counterparty to the relevant transaction; or whether two distinct CASP services are provided, dominated by the fiduciary duty of best execution emanating from the CASP service of execution though.

Self-contracting is possible both in the context of the general agency provisions[56], where an agent may self-contract by also being the counterparty to the transaction in question, but is also possible in the context of CASP services as it emanates from recital nr.(87) of MiCAR[57].

As per the statement in the said recital: ‘When a crypto-asset service provider executing orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients is the client’s counterparty, there might be similarities with the services of exchanging crypto-assets for funds or other crypto-assets. Yet in the execution of orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients, the crypto-asset service provider should always ensure that it obtains the best possible result for its client, including when it acts as the client’s counterparty, in line with its best execution policy.’

It emanates from the aforesaid that there is no requirement for a different person of the counterparty from that of the executing entity, Nevertheless, the fact that the transaction in question takes place as a result of a previous financial intermediation in the form of the CASP service of execution produces legal results. These are the observance by the self-contracting CASP of the fiduciary duty of the best execution obligation prior to the provision of the CASP service of exchange.

In essence, the conclusion of the transaction in question with the executing CASP acting also as counterparty trading against proprietary capital is possible; provided that the CASP’s best execution policy[58] has been previously observed , given the CASP’s capacity as the client’s agent when providing the CASP service of execution.

Thus, where a CASP executes a transaction while also being the client’s counterparty trading against proprietary capital two distinct CASP services will be provided:

| Scenario | Execution as a CASP Service | Matched Principal Trading (MPT) |

| CASP executes client order with third party | Agent | One service: Execution on behalf of client |

| CASP executes client order with itself (self-contracting) | Agent + Counterparty | Two services: (1) Execution on behalf of client (2) Trading against proprietary capital |

| CASP fails to follow best execution policy before trading with itself | Breach of fiduciary duty | Not compliant with MiCAR Article 78 |

Best execution and other regulatory aspects of the CASP service of execution

1. Best execution

1.1 Best execution as a specific fiduciary duty

As the client’s agent, the CASP providing execution is subject to a specific fiduciary duty, over and above the general fiduciary duty incumbent on all types of CASPs to act in the best interest of their clients[60]: The said specific duty consists of the CASP taking all necessary steps to obtain, while executing orders, the best possible result for its clients under consideration of relevant factors[61].

It is the concept of ‘best execution’[62], already known from MiFID II[63]. It serves investor protection purposes[64], which is the case under MiCAR as well, given the client-centric MiCAR formulation of this fiduciary duty as‘…to obtain…the best possible result for their clients…’, which is in alignment with the respective MiFID II formulation. However, the MiFID II[65] axiom of ‘total consideration’ as benchmark of best execution for retail clients is not present under MiCAR.

The reason therefore being that MiCAR, unlike MiFID II, does not categorise CASP clients into retail and professional nor vary regulatory protection standards depending on the aforesaid categorisation[66][67]. As regards the prohibition of remuneration for order routing provided for in MiFID II[68], the respective MiCAR prohibition is laid down in the current draft Level 2[69] measures and applies, for the avoidance of doubt, to both RTO and execution[70], as per ESMA’s guidance.

1.2 Abrogating specific client instructions

Despite the provision for the specific fiduciary duty of best execution, executing CASPs shall not be required to take the necessary steps to obtain the best possible result for their clients, in case where the order is executed following specific instructions from the client[71]. The discharge from the said obligation is aligned with the client’s capacity as principal, so that it is reasonable that such protection be established for the client’s sake but not against the client-principal’s will.

This means that the legal capacity as principal is not bypassed by regulatory considerations motivated by investor protection. The said conclusion is also confirmed by the draft Level2 measures whose wording is identical for both notifying[72] as well as for CASP authorisation applying[73] entities and requires them to disclose in their execution policy: ‘… how the client is warned that any specific instructions from a client may prevent…from taking the steps that it has designed and implemented in its execution policy to obtain the best possible result for the execution of those orders in respect of the elements covered by those instructions;’.

Thus, the initial fiduciary duty to devise steps for obtaining the best possible result shrinks into a duty to merely address a warning to the client, in case of specific client instructions. The preceding draft Level2 wording also clarifies that the Level1 term of ‘specific instructions’ has a thematic content: The term specific refers to elements of the order viewed individually and not to the order as a whole.

Within the context of ideas described in the preceding paragraph, following issue arises:

Can specific client instructions lead to the aforementioned shrinking of the CASP’s initial fiduciary obligation towards the client/principal, even where such instructions are highly likely or manifestly erroneous, hence against the client obtaining the best possible result by default?

It could be alleged that the requirement for ‘taking all necessary steps’ is procedural in nature, as the term ‘taking steps’ suggests, so that the obligation for obtaining the best possible result still applies.

However, such argumentation does not consider the causal nexus between means, on the one hand, and end, on the other hand: If ‘all necessary steps’ are omitted, the best possible result can only be attained randomly if not at all. This means that Art.78 para.1 of MiCAR only provides the legal basis for the CASP to issue a warning in case of highly likely or even manifestly erroneous client instructions.

However, highly likely or manifestly erroneous instructions, i.e. instructions (highly probably) eliminating the client’s possibility to obtain the best possible result, are against the client’s best interest. This means that the general, all-CASP encompassing obligation under Art.66 of MiCAR to act in the client’s best interest becomes applicable.

Thus, there is a legal basis obliging the CASP, apart from warning the client under Art.78 of MiCAR, to still try to obtain the best possible result, namely the general fiduciary duty to act in the client’s best interest, which is inspired by consumer protection standards[74].

This is also corroborated from the previously mentioned draft Level2 wording that the CASP ‘may [be] prevent[ed]’, hence not exempted from obtaining the best possible result for a client addressing specific instructions.

2. Order execution policy

2.1 Key aspects of the order execution policy

2.1.1 Execution policy and execution arrangements

To the end of achieving best execution, CASPs shall establish and implement execution arrangements, in particular an order execution policy[75]. Nevertheless, while some guidance is provided in relation to the purpose of the ‘execution policy’[76], the text is silent in relation to the meaning of this term as well as of that of ‘execution arrangements’.

This issue had been observed in the context of MiFID as well, where relevant guidance[77] has been provided though. As per the said guidance, ‘execution policy’ is an aspect of ‘execution arrangements’, namely a ‘statement incorporating the most important and/or relevant aspects[78] of the MiFID firm’s overall ‘execution arrangements’.

The fact that the ‘execution policy’ is a significant part of the CASP’s ‘execution arrangements’ also in the context of MiCAR[79] is inferred from the wording ‘…shall establish and implement effective execution arrangements. In particular…an order execution policy…’.

Given this connection, the guidance as to the meaning of the term ‘execution arrangement’ under MiFID II also becomes relevant for MiCAR purposes: ‘…execution arrangements are the means that an investment firm employs to obtain the best possible results, including its strategy, practices and procedures…’.

In addition to devising execution arrangements, in particular an order execution policy, CASPs are faced with the ongoing obligation to ‘monitor the effectiveness of their order execution arrangements and order execution policy in order to identify and, where appropriate, correct any deficiencies in that respect.’[80].

Key Takeaway: The order execution policy is an aspect of the execution arrangements incorporating the most important and relevant aspects of the CASP’s overall execution arrangements. CASPsmust monitor their effectiveness and correct any deficiencies.

2.1.2 Providing appropriate and clear information on the execution policy and the meaning of ‘significant changes thereto’

While the order execution policy as such has to be submitted to the competent NCA both by notifying entities[81] as well as by CASP authorisation applicants[82], there is no similar requirement as regards the content of the execution policy to be communicated to clients:

The requirement for providing clients with ‘appropriate and clear information’ on the CASP’s order execution policy implies that the CASP is not obliged to disclose its execution policy in full.

Once again, the rationale for this legislative choice can be found in previous guidance in the context of MiFID, which is relevant for MiCAR[84] purposes as well: ‘By requiring disclosure of information on the firm’s (execution) policy rather that its detailed execution approach, MiFID aims to strike a balance between requiring firms to disclose a lengthy trading manual (which would be of limited utility to clients) and a description that is too high level to facilitate client understanding of a firm’s execution process.’[85]

This practically means that two sets of documented information in relation to the order execution policy have to be prepared by executing CASPs, namely one lengthy, technical and detailed for submission to the NCA and one for disclosure to clients.

In addition, the term ‘significant change thereto’ employed in Art.78 para.3 first sentence of MiCAR is to be perceived as a reference to a significant change to the clear and appropriate information on the order execution policy; and not to such a change to the order execution policy as such.

Changes to the order execution policy as such as well as to execution arrangements in general, are caught by Art.78 para.6 third sentence of MiCAR requiring CASPs to ‘notify clients with whom they have an ongoing client relationship of any material changes to their order execution arrangements or order execution policy’.

Otherwise, following logical inconsistency occurs: The Level1 wording would require the provision of ‘appropriate and clear information’ in relation to changes to the order execution policy on the one hand; and the draft Level 2[86] measures would require that such clear and appropriate information be reduced to a mere notification on the other hand, as CASP have to ‘notify them [their clients] of any material changes to their order execution policy;’.

Such an inconsistency would, apart from the logical issues, also create institutional issues as regards the relationship between Level1 and Level2 provisions, let aside the confusion caused because of this overlap in Art.78 para.3 and 6 of MiCAR respectively. Besides, the draft Level2 wording of ‘material change’[87] makes it clear that it refers to Art.78 para.6 third sentence of MiCAR and not to the ‘significant change’ under Art.78 para.3 first sentence of MiCAR.

This conclusion is further corroborated by following practical argument: Changes to the execution policy as such have to be communicated by CASPs only to clients ‘with whom they [CASPs] have an ongoing client relationship’[88]; whereas, a ‘significant change’ to the non-technical information under Art.78 para.3 of MiCAR has to be communicated to all clients[89]. The reason therefore being that only frequent traders have an interest in being informed of material changes to the lengthy, technical and operational document of the order execution policy and to the overall ‘strategy, practices and procedures’ forming the execution arrangements; conversely, for less frequently trading or even inactive clients the non-technical information is sufficient.

In a neighbouring context of ideas, the draft Level 2 measures[90] leave it up to the CASP to determine ‘the arrangements and procedures for how’ the notification of material changes to the order execution policy will take place.

To this end it has to be borne in mind that, unlike the requirement for the client’s prior consent to the order execution policy which has to be obtained in advance[91], material changes to the order execution policy are only to be notified. Thus, an electronic pop up message with the notification of the change in the client’s account is sufficient and less burdensome from an administrative perspective. From an a maiore ad minus perspective, if this is possible for relevant changes to the complex document of the order execution policy, it is even more possible for the relevant changes to the non-technical information on the order execution policy.

Key Takeaway: CASPs prepare one detailed and technical document for the NCA and one simplified version for clients. A significant change concerns client information, while material changes concern the order execution policy or arrangements and must be notified to ongoing clients.

2.1.3 Timing for obtaining prior consent to the order execution policy

Finally, while a client’s ‘prior consent’[92] on the CASP’s order execution policy has to be obtained, MiCAR does not specify at Level1 prior to which point in time the said consent has to be obtained: Shall the client’s prior consent have to be obtained upon the client’s onboarding, i.e. upon the client’s adherence to the CASP’s terms of service and the respective client account opening; or upon the CASP undertaking the execution of the first transaction on behalf of the client, which may take place at a later stage following the client’s onboarding? The draft Level2[93] measures provide further guidance in this respect, as they require that ‘…the client has provided consent on the execution policy prior to the execution of the order.’. This practically means that the latest point in time for obtaining the client’s ‘prior consent’ is prior to undertaking the execution of the client’s first order.

The said execution may not be simultaneous with but follow the client’s onboarding by the CASP. However, this option would be associated with enhanced administrative burden for the CASP, as it would have to monitor the client’s account activity.

For this reason it is recommendable to embed the requirement for the client’s prior consent to the CASP’s execution policy in the CASP’s terms of service, so as to obtain it, upon onboarding the client.

Key Takeaway: The latest point for obtaining the client’s prior consent is before executing the first order. It is recommendable to embed this requirement in the CASP’s terms of service upon onboarding.

2.1.4 Demonstrating agreed and compliant execution

Similarly to the respective MiFID II[94] wording, a CASP shall be able to demonstrate to its clients, at their request, that it has executed their orders in accordance with the CASP’s order execution policy; compliance therewith has to be demonstrated to the relevant NCA as well[95].

It emanates therefrom that the focus of this obligation is not on the required demonstration as such, as it is conditional upon a relevant request being addressed by the client and/or the relevant NCA (as the case may be); but on the ability of the CASP to carry out such demonstration whenever so requested.

This understanding is corroborated by the draft Level2[96] measures, which do not provide for guidance as to the content of the required demonstration, but require ‘the arrangements to demonstrate compliance with Article 78 of Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 to the competent authority…’.

This means that the demonstration towards the relevant NCA encompasses ‘arrangements’, including thus the relevant procedures. However, there is no reference to ‘arrangements’ in the demonstration to be carried towards the requesting client.

As regards the CASP’s ‘ability’ to carry out the required demonstrations towards clients and NCAs, it should be borne in mind that a CASP has access to all relevant execution data, given MiCAR’s centralised approach.

Thus, the CASP is by definition able to carry out the required demonstrations, as it is considered to have access to the relevant data at all times. Subsequently the wording ‘shall be able’ of Art.78 para.4 of MiCAR is not to be perceived as referring to the CASP ensuring availability of all required data, as this is taken for granted; but to the means the CASP will use for carrying out the said demonstrations, e.g. automated RegTech tools, manual extraction etc. Finally, as regards the content of the demonstrations, in question, the benchmark shall be the CASP’s order execution policy[97], unless and until further regulatory guidance is provided to this end.

Key Takeaway: A CASP shall be able to demonstrate to clients and the competent authority compliance with its order execution policy upon request. The wording “shall be able” refers to the means used, such as automated RegTech tools or manual extraction, since it is taken for granted that the CASP has access to the relevant execution data.

2.2 About the content of the order execution policy

As to the content of the order execution policy it ‘shall, amongst others, provide for the prompt, fair and expeditious execution of client orders and prevent the misuse by the crypto-asset service providers’ employees of any information relating to client orders.’[98].

Given that the order execution policy aims at ensuring compliance with the CASP’s best execution obligation, the question that arises is whether the terms ‘prompt, fair and expeditious execution’ fall under the topic of best execution; or whether these terms constitute additional content of the order execution policy, as to be deducted from the formulation ‘The order execution policy shall, amongst others…’ and what their meaning can be.

In limine and given the overall Mifidisation of the provisions of Art. 78 of MiCAR, it needs to be borne in mind that there is an established legislative precedence in employing the terms ‘prompt, fair and expeditious execution’.

More specifically, the said terms have been provided for in the context of the client order handling rules both under the repealed MiFID I[99] initially as well as under its successor MiFID II[100]. As per relevant guidance[101], client order handling is to be perceived as a regulatory obligation next to the best execution and other regulatory obligations. This is also aligned with the MiCAR formulation ‘…an order execution policy …to comply with paragraph 1 [best execution]. The order execution policy shall, amongst others, provide for the prompt, fair and expeditious execution of client orders…’.

It emanates therefrom that prompt, fair and expeditious execution is something ‘amongst others’ than best execution in the context of MiCAR as well. In addition to the textual arguments, the meaning of the terms fair and expeditious is also to be perceived as something different from that of best execution: ‘Fairness and expediency for the purposes of this provision [client order handling] are to be understood not by reference to the quality of execution of a given client order relative to conditions in the wider marketplace (‘best execution’), but relative to the handling of other client orders or proprietary transactions of the investment firm.’[102]. It emanates from the aforesaid that, while best execution has an extrovert content, namely the execution of the order in relation to prevailing market factors[103], prompt and expeditious execution are interna corporis, as these relate to the internal handling of orders by the CASP. As to the term ‘prompt’ it is self explanatory that it does not refer to best execution but to timely execution[104], i.e. to internal order handling mechanisms in place[105] and not external market factors.

Thus, the requirement for CASPs to include procedures for prompt, fair and expeditious execution in their order execution policy is additional to the steps for obtaining best execution.

As regards the reference to CASPs preventing ‘the misuse by the crypto-asset service providers’ employees of any information relating to client orders.’ relevant examples of unacceptable practices vis-à-vis best execution obligations and client order handling requirements are provided by means of guidance in the context of MiFID II[106].

3. The concept of ‘execution venues’

While the term ‘trading platform’ laid down in Art.78 para.5 is defined in MiCAR[107] and encompasses multi-lateral trading systems, the term ‘execution venues’[108] remains undefined, unlike its MiFID II notional homologue[109].

This definitional silence takes place both at the level of MiCAR as well as at that of the draft Level2[110] measures. Given that a trading platform is a multilateral system centrally operated by the relevant operator, whereas Art. 78 para.5 of MiCAR provides for execution ‘outside a trading platform’, the remaining additional possibilities for achieving execution, i.e. other execution venues, can be bilateral arrangements or decentralised platforms. While factual findings corroborate and substantiate this conclusion[111], legal arguments derived from MiCAR also serve towards the same end.

More specifically:

a) Recital nr.(87) of MiCA lays down that ‘When a crypto-asset service provider executing orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients is the client’s counterparty… the crypto-asset service provider should always ensure that it obtains the best possible result for its client, including when it acts as the client’s counterparty…’.[112]. This means that it is possible for a CASP to execute a client’s instruction with itself over-the-counter[113]. Thus, the CASP itself can be considered as an ‘execution venue’, since the trade is concluded ‘outside a trading platform’.

b) The aforesaid constellation can be enriched with a decentralized ‘twist’, since ‘…financial services may also be provided through decentralized applications…with minimal or no intermediaries’ involvement.’[114]. Indeed, the draft Level2 measures require both notifying entities as well as CASP applicants to disclose ‘…any exchange of crypto-assets for funds and other crypto-asset activities that the [notifying entity or CASP applicant, as the case may be] intends to undertake, including through any decentralised finance applications with which the [notifying entity or CASP applicant, as the case may be] wishes to interact on its own account.’[115]. Thus, it is possible for a CASP to qualify as an execution venue also when seeking a crypto-asset in a decentralized environment, in order to subsequently execute the client’s order with the CASP itself as counterparty; or to engage in an MPT as counterparty to the client and the DeFi trading peer at the same time.

Thus, the term execution venues under MiCAR is to be perceived as also encompassing, over and above trading platforms, the aforesaid execution constellations. However, CASPs shall ‘In particular…assess, on a regular basis, whether the execution venues included in the order execution policy provide for the best possible result for clients or whether they need to make changes to their order execution arrangements.’[116]

As regards required disclosures in case where the CASP’s order execution policy provides for the possibility that client orders might be executed outside a trading platform, the clients shall be informed thereof in advance[117] and their prior express consent must be obtained[118].

Given that the said possibility is part of the CASP’s overall order execution policy, to which the client must anyway consent in advance[119], the term ‘prior express consent’ is rather to be understood as ‘prior additional and specific consent’. Thus, the said specific consent must be obtained, in addition to the general consent required under Art.78 para.3 third sentence of MiCAR. As to the timing where this additional specific consent has to be obtained, MiCAR provides for the possibility of it being obtained ‘either in the form of a general agreement or with respect to individual transactions.’[120].

This practically means that this additional specific consent in question must be obtained either when the client consents to the CASP’s terms of service or on an ad hoc basis prior to such a transaction being undertaken.

However, given the administrative burden associated with an ad hoc prior consent[121], it is recommendable to obtain such consent jointly with the general consent to the CASP’s order execution policy, upon the client’s adherence to the CASP’s terms of service.

[1] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Questions and Answers On MiFID II and MiFIR investor protection and intermediaries topics, ESMA35-43-349, 15 December 2023, p. 28 Answer to Question nr.14 available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma35-43-349_mifid_ii_qas_on_investor_protection_topics.pdf, p: ‘…sends an order to an entity for execution (broker)…’

[2] INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF SECURITIES COMMISSIONS (IOSCO), Policy Recommendations for Crypto and Digital Asset Markets-Final Report, FR11/2023/16 November 2023, p.5 and p.19 available at https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD747.pdf : ‘…a CASP may actually be operating as a trading intermediary (a broker or dealer…a CASP…may instead operate as an intermediary such as a broker or dealer…’; Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, Non-bank financial intermediaries and financial stability, BIS Working Papers No 972, October 2021 (revised January 2022), p.2 Figure1, available at https://www.bis.org/publ/work972.pdf; Maia, Guilherme/Vieira dos Santos, João, MiCA and DeFi (‘Proposal for a Regulation on Market in Crypto-Assets’ and ‘Decentralised Finance’), July 1 2021, p.15, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3875355; Central Bank of Ireland, Brokers/Retail Intermediaries, available at https://www.centralbank.ie/regulation/industry-market-sectors/brokers-retail-intermediaries : ‘A broker / retail intermediary is a regulated firm that engages in intermediation activities relating to certain financial products…’.; The Law Commission, Fiduciary Duties of Investment Intermediaries, Law Com No350, 24/06/2014 , p. ix available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7ebcdded915d74e33f21b2/41342_HC_368_LC350_Print_Ready.pdf : ‘Broker An individual or organisation that acts as an intermediary between a buyer and seller, usually in return for the payment of a commission.’.

[3] Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, Non-bank financial intermediaries and financial stability, BIS Working Papers No 972, October 2021 (revised January 2022), p.2 Figure 1 and p. 4.

[4] Deducted from the notional limb of execution under Art.3 para.1 nr.(21) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40: ‘…or the subscription on behalf of clients for one or more crypto-assets…’, since the term ‘subscription’ refers to initial offerings by default..

Recital nr.(26) of ECSPR 2020/150, OJ L 347,1; European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Questions and Answers On the European crowdfunding service providers for business Regulation ,, p.12f. available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma35-42-1088_qas_crowdfunding_ecspr.pdf : ‘[crowdfunding platform operators] should operate as neutral intermediaries between clients on their crowdfunding platforms…and…not impair its neutrality vis-à-vis its clients.’.

[6] Cornell Law School LLI Legal Information Institute, escrow agent, available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/escrow_agent#:~:text=The%20escrow%20agent%20is%20an,a%20natural%20person%20or%20entity : ‘The escrow agent is an independent third party in charge of holding the assets, documents, and/or money in escrow until the contractual condition is fulfilled in the terms and conditions established by the parties in the escrow agreement…the escrow agent has fiduciary duties with all the parties to the escrow agreement…’.

[7] Article 3 para.1 nr.(39) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40: ‘‘client’ means any natural or legal person to whom a crypto-asset service provider provides crypto-asset services;’.

[8] European Commission, Frequently Asked Questions on MiFID: Draft implementing “level 2” measures, MEMO/06/57, 06 February 2006, Part II section 1.1.1 available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/MEMO_06_57 : ‘MiFID therefore also places considerable emphasis on the fiduciary duties of firms towards their clients – i.e. their obligation to put their clients’ interests first. It imposes a number of specific obligations on firms, including execution of client orders on the best possible terms (“best execution”)…’, a concept which is also reflected in Art.78 para.1 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[9] Recital nr.(22) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40; Securities and Markets Stakeholder Group (SMSG), Advice: SMSG advice to ESMA on its Consultation Paper on Technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), 25 March 2024, p.47 para. 27 available as Annex II at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-03/ESMA18-72330276-1634_Final_Report_on_certain_technical_standards_under_MiCA_First_Package.pdf : ‘MiCA Regulation is an entity-based set of rules (e.g., the CASP authorisation process or the CASP conflicts of interests).’. The same view is expressed in the said advice in summary form on p.42 of the same document; European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Advice: Initial Coin Offerings and Crypto-Assets, ESMA50-157-1391, 9 January 2019, p.44 para.190 available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma50-157-1391_crypto_advice.pdf : ‘Centralized platforms, which seem to be the dominant model today…’.

[10] Maia, Guilherme/Vieira dos Santos, João, MiCA and DeFi (‘Proposal for a Regulation on Market in Crypto-Assets’ and ‘Decentralised Finance’), July 1 2021, p.12: ‘…some degree of centralisation, which generally means having an identifiable intermediary that would be the liable entity within MiCA.’.

[11] Zetzsche, Dirk Andreas/Sinnig, Julia, The EU Approach to Regulating Digital Currencies, Law and Contemporary Problems, Vol. 87, No. 2, 26 January 2024, p.23 available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4707830 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4707830; Annunziata, Filippo, An Overview of the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR), European Banking Institute Working Paper Series no. 158, 11 December 2023 p.56 with reference in Fn. Nr.80 to M. T. PARACAMPO, I prestatori di servizi su cripto-tività. Tra mifidizzazione della MICA e tokenizzazione della Mifid, Turin, 2023, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4660379 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4660379

[12] Art.78 para.1 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[13] Art.78 para.1 subpara.2 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[14] Art.78 para.4 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[15] Art.78 para.5 in conjunction with para.6 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40. The term ‘execution venue’ is also provided for in the draft Level 2 measures: European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024, Annex III p.61 Art.9 lit.(b) of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 60(13) of MiCA available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-03/ESMA18-72330276-1634_Final_Report_on_certain_technical_standards_under_MiCA_First_Package.pdf and European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA 18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024, Annex II p.95 Art.15 lit.(b) of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 62(5) of MiCA.

[16] As it also emanates from the wording of Art.78 para.5 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40: ‘Where the order execution policy provides for the possibility that client orders might be executed outside a trading platform…’.

[17] Art.4 para.1 nr.(24) of MiFID II 2014/65, OJ L 173, 349: ‘trading venue’ means a regulated market, an MTF or an OTF;’.

[18] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation Paper Review of the MiFID II framework on best execution reports, ESMA35-43-2836, 24 September 2021, p.6 Fn.3 , available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma35-43-2836_cp_-_best_execution_reports.pdf : ‘Execution venues include trading venues, systematic internalisers, market makers and other liquidity providers (Article 1 RTS 27, in line with the relevant best execution requirements in the MiFID II delegated regulation).’.

[19] Illustratively Maia, Guilherme/Vieira dos Santos, João, MiCA and DeFi (‘Proposal for a Regulation on Market in Crypto-Assets’ and ‘Decentralised Finance’), July 1 2021, p.4 : ‘An easy demonstration that MiCA is inspired in financial legislation is to observe that most of the crypto-assets services are the same as most of MiFID II services’.

[20] Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, Translated by G. R. G. Mure (accessed 17.04.2024), available at https://www.logicmuseum.com/authors/aristotle/posterioranalytics/posterioranalytics.htm : ‘ALL instruction given or received by way of argument proceeds from pre-existent knowledge.’.

[21] European Commission, Fintech, distributed-ledger technology and the token economy (accessed 17.04.2024), available at https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/access-finance/policy-areas/fintech-distributed-ledger-technology-and-token-economy_en : ‘The Commission considers DLT as a breakthrough technology that is key for the EU’s competitiveness.’.

[22] Art.3 para.1 nr.(5) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40,: ‘crypto-asset’…is able to be transferred…’ and recital nr.(17) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40: ‘Digital assets that cannot be transferred to other holders do not fall within the definition of crypto-assets. Therefore, digital assets that are accepted only by the issuer or the offeror and that are technically impossible to transfer directly to other holders should be excluded from the scope of this Regulation. An example of such digital assets includes loyalty schemes where the loyalty points can be exchanged for benefits only with the issuer or offeror of those points.’

[23] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation paper On the draft Guidelines on the conditions and criteria for the qualification of crypto-assets as financial instruments, ESMA75-453128700-52, 29 January 2024,P.11 paras 33ff. available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-01/ESMA75-453128700-52_MiCA_Consultation_Paper_-_Guidelines_on_the_qualification_of_crypto-assets_as_financial_instruments.pdf : ‘Negotiability is also a key criterion. Although, there is currently no definition in Union law…this would imply for crypto-assets to be transferable… Therefore, for a crypto-asset to be recognised as a transferable security under MiFID II, it must be negotiable, transferable…’.

[24] Combined reading of Art.2 para.3 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 and of recital 10f. of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[25] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation paper On the draft Guidelines on the conditions and criteria for the qualification of crypto-assets as financial instruments, ESMA75-453128700-52, 29 January 2024 (accessed 17.04.2024), p.11 para 33 : ‘Negotiability on capital market also presupposes fungibility which has to be measured having regard to the capability of the crypto-asset [qualifying as a transferable security]to express the same value per unit.’.

[26] The so-called notifying entities, which are exempted from authorisation as a CASP but still subject to relevant compliance pursuant to Article 60 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[27] E.g. AIFMs under Art.6 para.4 of the Directive 2011/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on Alternative Investment Fund Managers and amending Directives 2003/41/EC and 2009/65/EC and Regulations (EC) No 1060/2009 and (EU) No 1095/2010, OJ L 174, 1 and UCITS management companies under Art.6 para.3 of the Directive 2009/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS) (recast), OJ L 302, 32 respectively.

[28] See for instance Art.60 para.3 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40. However, it should be borne in mind that notifying entities are only exempted from authorization as a CASP, but not from compliance with the MiCAR CASP rules, ass per Art.60 para.10 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40. For a full list of the notifying entities and of the respective CASP equivalent services per notifying entity, see Art.60 paras. 1-6 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150.

[29] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation Paper: Technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), ESMA74-449133380-425, 12 July 2023, p.10 paras. 8ff. available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-07/ESMA74-449133380-425_MiCA_Consultation_Paper_1st_package.pdf .

[30] European Commission, MEMO Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II): Frequently Asked Questions, 15 April 2014, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_14_305 : ‘It [MiFID] is a cornerstone of the EU’s regulation of financial market.’.

[31] INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF SECURITIES COMMISSIONS (IOSCO), Policy Recommendations for Crypto and Digital Asset Markets-Final Report, FR11/2023/16 November 2023, p. 52 : ‘Respondents agreed [with IOSCO] that the same standards should be applied to the crypto-asset market as that applied to traditional financial markets, including around best execution and disclosure.‘.

[32] Financial Stability Board (FSB), Regulation, Supervision and Oversight of Crypto-Asset Activities and Markets Consultative document, 11 October 2022, p.4 and 7, available at https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P111022-3.pdf . More specifically it is noted on p.4 that: ‘The crypto-asset ecosystem features a wide range of functions and activities, many of which resemble those in the traditional financial system.’ and on p.7 section 2 that: ‘Given the similarity between economic functions and activities in the crypto-asset market and the traditional financial system, many existing international policies, standards, and jurisdictional regulatory frameworks are relevant for crypto-asset activities.’.

[33] Financial Stability Institute (FSI) of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), FSI Insights on policy implementation Crypto, tokens and DeFi: navigating the regulatory landscape, No 49, May 2023, p.27 para.68, available at https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights49.pdf: ‘There are significant similarities between cryptoasset service provision activities and those in the traditional financial system…This suggests that the same standards and policies that apply to traditional financial intermediaries should also be applied to cryptoasset service providers, taking into account any novel aspects of these assets.’.

[34] Art.53 para.3 of MiFID II 2014/65, OJ L 173, 349 allows regulated markets to admit as members or participants investment firms, credit institutions and other persons who satisfy certain requirements on substance, resources and trading ability.

[35] Qualifying as trading platforms under Art.3 para.1 nr.(18) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 due to their multilateral nature and their order-matching function.

[36] It should be borne in mind that MiCAR does not categorise clients into retail or professional or eligible counterparties, unlike MiFID, so that all traders, even if they display retail characteristics, are equally allowed to directly trade on the platforms of the crypto-exchange.

[37] See recital nr.(26) of Regulation (EU) 2022/858 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on a pilot regime for market infrastructures based on distributed ledger technology, and amending Regulations (EU) No 600/2014 and (EU) No 909/2014 and Directive 2014/65/EU, OJ L 151, 1: ‘At present, traditional multilateral trading facilities are allowed to admit as members or participants only investment firms, credit institutions and other persons who have a sufficient level of trading ability and competence and who maintain adequate organisational arrangements and resources. By contrast, many platforms for trading crypto-assets offer disintermediated access and provide direct access for retail investors’ and Art.4 para.2 of the DLT PilotR 2022/858, OJ L 151, 1: ‘In addition to the persons specified in Article 53(3) of Directive 2014/65/EU… the competent authority may permit that operator to admit natural and legal persons to deal on own account as members or participants…’; Coinbase, International Exchange available at https://www.coinbase.com/international-exchange : ‘Our…trading system…provides users with direct access…’

[38] European Commission, COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-assets and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937, SWD(2020) 380 final, 24.09.2020, p. 15, available at eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020SC0380 .

[39] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation Paper: Technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), ESMA74-449133380-425, 12 July 2023, p.125 Recital nr.(10) of draft RTS on identification, prevention, management and disclosure of conflicts of interest, available at: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-07/ESMA74-449133380-425_MiCA_Consultation_Paper_1st_package.pdf : ‘It may not always be clear to clients in what capacity or capacities the crypto-asset service provider is acting, especially as crypto-asset service providers may often be operating in a vertically integrated manner or in close cooperation with affiliated entities or entities of the same group… This is particularly relevant in situations where, for instance, the crypto-asset service provider is presenting itself as an exchange but actually engage in multiple activities such as operating a trading platform in crypto-assets, market-making or offering margin trading.’; INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF SECURITIES COMMISSIONS (IOSCO), Policy Recommendations for Crypto and Digital Asset Markets-Final Report, FR11/2023/16 November 2023, p.16: ‘Although often presenting themselves as “exchanges”, many CASPs typically engage in multiple functions and activities under ‘one roof’ – including exchange services operating a trading venue, brokerage, market-making and other proprietary trading, offering margin trading, custody, clearing, settlement…’; Financial Stability Institute (FSI) of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), FSI Insights on policy implementation Crypto, tokens and DeFi: navigating the regulatory landscape, No 49, May 2023, p.26 para.64 : ‘Non-bank centralised entities such as cryptoasset exchange and trading platforms that provide vertically integrated cryptoasset activities (eg issuance, exchange, trade, payments, lending, borrowing), usually referred to as “crypto conglomerates”, have emerged as key players in cryptoasset markets.’; Financial Stability Board (FSB), Regulation, Supervision and Oversight of Crypto-Asset Activities and Markets Consultative document, 11 October 2022 , p.19/77 section 3.7: ‘One prominent feature of the crypto-asset market structure is that service providers often engage in a wide range of functions. Some trading platforms, besides their primary functions as exchanges and intermediaries, also engage in custody, brokerage, lending, deposit gathering, market-making, settlement and clearing, issuance distribution and promotion. Some trading platforms also conduct proprietary trading…‘; European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Advice: Initial Coin Offerings and Crypto-Assets, ESMA50-157-1391, 9 January 2019 p.44 para, 190: ‘Centralized platforms, which seem to be the dominant model today, require users to deposit their assets with the platform prior to trading…The rest, e.g., the matching of orders, the execution of orders and the corresponding transfer of ownership between users, is typically recorded in the books of the platform only (off-chain).’; See the offering of Kraken, which is a crypto-exchange, Kraken, Kraken Institutional OTC

Available at https://www.kraken.com/institutions/otc : ‘Chat securely with our trade desk to confirm the asset, lot size and price of your trade. Benefit from white-glove, personalized service from initial consultation to trade execution.’.

[40] As per Art.3 para.1 nr.(18) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 a trading platform ‘…bring[s] together or facilitate[s] the bringing together of multiple third-party purchasing and selling interests in crypto-assets…’

[41] However, there is the limitation introduced by Art.76 para.6 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 as regards market making activities by trading platforms.

[42] Those falling under Art.60 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[43] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation Paper: Technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), ESMA74-449133380-425, 12 July 2023, p.10 para.10f.: ‘In other words, MiCA is paying deference to the existing authorisation… The rationale for this decision is that notifying financial entities are already strictly regulated and already have the infrastructure in place to provide financial services’

[44] Emanating from the term ‘subscription’ provided for in Art.3 par.1 nr.(21) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 : ‘…or the subscription on behalf of clients for one or more cryptoassets…’

[45]Maia, Guilherme/Vieira dos Santos, João, MiCA and DeFi (‘Proposal for a Regulation on Market in Crypto-Assets’ and ‘Decentralised Finance’), July 1 2021, p.15: ‘Additionally, there are crypto-assets services in MiCA that only entail a simple interaction with the clients, namely the reception and transmission of orders on behalf of third parties, defined in MiCA as the reception from a person of an order to buy or to sell one or more cryptoassets or to subscribe for one or more crypto-assets and the transmission of that order to a third party for execution.’; European Union Emissions Trading System (EUETS), Execution of orders on behalf of clients (MiFID definitions), Published: 23 January 2015 Last Updated: 25 September 2021 available at https://emissions-euets.com/internal-electricity-market-glossary/758-execution-of-orders-on-behalf-of-clients-mifid-definitions : ‘The execution of an order on behalf of a client can be opposed to simply arranging the relevant deal…’;

[46] The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR), Best Execution under MiFID Questions & Answers, Ref: CESR/07-320, May 2007, p.26 para.25 available at: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/2015/11/07_320.pdf : ‘Execution of a client order or a decision to deal is always carried out when an investment firm is the last link in the chain of intermediaries between the client order and an execution venue…’.

[47] See for instance Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (German Civil Code) §164 BGB.

[48] An illustrative presentation of this difference in the context of financial services can be found in the response of the EU Commission’s services in The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR), Best Execution under MiFID Questions & Answers, Ref: CESR/07-320, May 2007, p.26 para.24 : ‘There should be a clear regulatory distinction between a firm that is authorised both to receive and transmit orders and to execute them and firm that may only receive and transmit client orders for execution to another investment firm. The latter firm may not in any way alter the instructions as it transmits them to another firm for execution or further transmission.’.

[49] This is why in case of execution the financial intermediary is deemed to be dealing as an agent, unlike cases of proprietary trading where it is deemed to be dealing as a principal. Quite illustrative is also EFAMA’s reply to ESMA’s Discussion paper on draft RTS and ITS under the Securities Financing Transaction Regulation European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA). EFAMA’s reply emphasizes that the term ‘agent’ reflects the real nature of the intermediary when providing execution instead of the industry jargon ‘broker’, which may encompass other dealing capacities as well. See European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA), EFAMA’s reply to ESMA’s Discussion paper on draft RTS and ITS under the Securities Financing Transaction Regulation, [16-4033], 25 April 2016 p.4 of 23, available at https://www.efama.org/sites/default/files/publications/EFAMA_reply_ESMA_DP_SFTR_0.pdf : ‘We believe that the use of the term “broker” for any intermediary that acts on behalf of a counterparty (paragraph 97) is not appropriate…We would therefore strongly suggest ESMA to replace it with e.g. the terms of “executing agent“.’.

[50] Art.78 para.1 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[51] The fact that the executing CASP is an agent and not a counterparty, when providing execution, is without prejudice to the constellation of the CASP acting as agent by providing the CASP service of execution and also acting as principal by concluding the transaction with itself. See also section I.C.2 below herein.

[52] Art.3 para.1 nr.(40) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[53] Also known as back-to-back trading or riskless principal ‘riskless principal’ trading. Illustratively The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR), TECHNICAL ADVICE: CESR Technical Advice to the European Commission in the context of the MiFID Review – Transaction Reporting, Ref.: CESR/10-808, 29 July 2010, p.6 para.23 available at: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/2015/11/10_808_technical_advice_mifid_review_transaction_reporting.pdf : ‘These principal transactions made by a firm on its own account and on behalf of the client may have different names across Europe (e.g. “riskless principal”, “back to back transaction”, “on account of client in firm’s name” and ”commissionaire”). Whilst these transactions do not appear as agency transactions, they are still executed on behalf of a client rather than compromising the proprietary capital of the executing firm. This scenario typically happens when two matching trades are entered at the same time and price with a single party interposed following a client’s order.’.

[54] In this case, the CASP is not providing execution to the client at all, but deals directly with the client as principal. This has to be distinguished from the constellation where the CASP provides execution and also chooses to conclude the transaction with itself as principal as well. In the latter scenario two CASP services are being provided, namely that of execution and that of trading against proprietary capital (the CASP service of exchange).

[55] Namely the exchange services under Art.3 para.1 nr.(19)-(20) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[56] See e.g. §181 BGB (German Civil Code) known as „In-sich-Geschäft‘.

[57] See recital nr.(87) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[58] Art.78 para.2 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40. Illustratively described in Recital nr.(91) of MiFID II 2014/65, OJ L 173, 349: ‘It is necessary to impose an effective ‘best execution’ obligation to ensure that investment firms execute client orders on terms that are most favourable to the client. That obligation should apply where a firm owes contractual or agency obligations to the client.’

[59] Art.3 para.1 nr.(19)-(20) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 depending on whether the CASP’s client wants to sell or buy crypto-assets (as the case may be).

[60] Article 66 para.1 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 in conjunction with recital nr.(79) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40

[61] Article 78 para.1 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[62] The Association of Corporate Treasurers, Briefing note: MiFID (Market in Financial Instruments Directive) for Corporate Treasurers (Prepared with assistance from Slaughter and May), August 2007, available at https://www.treasurers.org/ACTmedia/mifid_0907.pdf p.21: ‘Following legal advice put out by the European Commission, FSA considers that the application of the best execution obligation is determined by whether a firm is executing an order on behalf [sic] of a client: in other words, when contractual or agency obligations are owed to the client so that the client is legitimately relying on the firm to protect its interests in relation to the terms of the transaction. So in dealer markets, where a client, relying on its own judgment, selects a dealer’s quote, best execution would not arise.’.

[63] See Art.27 of MiFID II 2014/65, OJ L 173, 349, in particular para.1 thereof.

[64] The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR), Best execution under MIFID-Public consultation, Ref: CESR/07-050b, February 2007, p.3 para.2 available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/2015/11/07_050b.pdf

[65] Art.27 para.1 second subpara of MiFID II 2014/65, OJ L 173, 349.

[66] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Questions and Answers On MiFID II and MiFIR investor protection and intermediaries topics, ESMA35-43-349, 15 December 2023 p.103 Answer2: ‘a private individual investor may be allowed to waive some of the protections afforded by the conduct of business rules set in MiFID II by requesting to be treated as a professional client.’; Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), Regulator Assessment: Qualifying Regulatory Provisions, 20 December 2017, available at https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/impact-assessments/mifid-ii-client-categorisation.pdf p.1 Fn.nr.1: ‘Retail clients are negatively defined as neither of the above, and are provided the greatest degree of protection…’.

[67] In recent years, the term ‘consumer’ is being used, in order to describe retail clients and emphasize their unsophisticated status and the need for enhanced regulatory protection: Illustratively, European Commission, Consumer financial services policy available at https://finance.ec.europa.eu/consumer-finance-and-payments/retail-financial-services/consumer-financial-services-policy_en#:~:text=Related%20links-,Definition,payment%20services : ‘Consumer financial services, also called retail financial services, are financial services offered to ordinary consumer… Consumers should be able to make well-informed decisions about financial products, and feel confident that they are adequately protected.’ The term ‘consumer’ is also relevant for MiCAR purposes, as per recital nr.(79) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40: ‘In order to ensure consumer protection…’.

[68] Art.27 para.4 of MiFID II 2014/65, OJ L 173, 349.

[69] As regards notifying entities the relevant provisions are laid down in European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation Paper: Technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), ESMA74-449133380-425, 12 July 2023, Annex II p.64 Art.9 lit.(c) of the draft RTS on the notification by certain financial entities of their intention to provide crypto-asset services. As regards CASP authorisation applications, the relevant provisions are provided for in European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Consultation Paper: Technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), ESMA74-449133380-425, 12 July 2023, Annex II p.95 Art.15 lit.(c) of the draft RTS on authorisation of crypto-asset service providers. The approach in the Consultation Paper was confirmed post consultation in European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024, p.61 Art.9(c) of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 60(13) of MiCA, Annex III available as at https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-03/ESMA18-72330276-1634_Final_Report_on_certain_technical_standards_under_MiCA_First_Package.pdf and in European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024 Annex V p.97 Art.15 lit.(c) of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 62(5) of MiCA.

[70] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Questions & Answers, ESMA_QA_2087 (accessed 30.03.2025), available at https://www.esma.europa.eu/publications-data/questions-answers/2087 : ‘Does the prohibition set out under Article 80(2) to receive “remuneration, discount or non-monetary benefit in return for routing orders received from clients” apply to the crypto-asset services of receiving and transmitting orders on behalf of clients as well as the execution of orders on behalf of clients? Yes. Article 80(2) provides that “crypto-asset service providers receiving and transmitting orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients shall not receive any remuneration, discount or non-monetary benefit in return for routing orders received from clients [… ] to another crypto-asset service provider”, meaning that it is prohibited to receive payments or benefits when providing the service of receiving and transmitting orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients. In addition, Article 80(2) provides that “crypto-asset service providers receiving and transmitting orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients shall not receive any remuneration, discount or non-monetary benefit in return for routing orders received from clients to a particular trading platform for crypto-assets…” meaning that it is prohibited to receive payments or benefits when providing the service of executing orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients.’

[71] Art.78 para.1 second subpara of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[72] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024, Annex III p.61 Art.9 lit.(f) of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 60(13) of MiCA.

[73] European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024 Annex V p.97 Art.15 lit.(f) of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 62(5) of MiCA.

[74] See the combined reading of recital nr.(79) of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40: ‘In order to ensure consumer protection, market integrity and financial stability, crypto-asset service providers should always act honestly, fairly and professionally and in the best interests of their clients.’ with Art.66 para.1 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150. As to the meaning of the term consumer see Fn.nr.(68) herein.

[75] Art.78 para.2 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[76] Art.78 para.2 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 third sentence: ‘The order execution policy shall, amongst others, provide for the prompt, fair and expeditious execution of client orders and prevent the misuse by the crypto-asset service providers’ employees of any information relating to client orders.’. Notifying entities shall read the aforesaid provisions in conjunction with European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024, Annex III p.61 Art.9 of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 60(13) of MiCA. As regards to CASP authorisation applications Art.78 para.2 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 shall be read in conjunction with European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024 Annex V p.97 Art.15 of the Draft RTS pursuant to Article 62(5) of MiCA.

[77] The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR), Best execution under MIFID-Public consultation, Ref: CESR/07-050b, February 2007, p.6 para.20.

[78] The use of plural is not by chance, since there are further aspects included in an execution policy, in addition to the execution as such. More specifically, as per The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR), Best execution under MIFID-Public consultation, Ref: CESR/07-050b, February 2007 (accessed 17.04.2024), p.6f para.22a the execution policy also includes the execution approach from the moment an order originates as well as the settlement of the order.

[79] Art.78 para.2 first sentence of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[80] Art.78 para.6 first sentence of MiCAR.

[81] Article 60 para.7 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 in conjunction with European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024, p.4 para.2: ‘where the notifying entity intends to provide the service of execution of orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients, a description of the execution policy;‘.

[82] Art.62 para.2 of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 in conjunction with European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), Final Report: Draft technical Standards specifying certain requirements of the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) – first package, ESMA18-72330276-1634, 25 March 2024 in p.8 para.18 ‘where the applicant CASP intends to provide the service of execution of order for crypto-assets on behalf of clients, a description of the execution policy.’.

[83] Art.78 para.3 first sentence of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40.

[84] The MiFID approach of striking a balance between lengthy trading manuals and a too high level description is also reflected in Art.78 para.3 second sentence of MiCAR 2023/1114 OJ L 2023/150, 40 which requires ‘sufficient detail and in a way that can be easily understood by clients’. Thus, MICAR requires, in alignment with the MiFID framework, sufficient detail, hence not a too high level description, and in a way that can be easily understood by clients, hence not a lengthy trading manual, which is a technical and operational document of the firm destined for internal use.