Over the past decade, financial literacy has evolved from an educational concern into a core pillar of the European Union’s economic and social agenda. According to the latest Eurobarometer survey (2023), fewer than one in five EU citizens demonstrate a high level of financial literacy. This gap underscores why financial competence has moved to the center of Europe’s economic and social policy discussions. It defines the capacity of citizens to navigate complexity, adapt to digital transformation, and contribute to a more resilient and inclusive economy. The following analysis explores how Europe—and particularly the CEE region—is redefining financial literacy through policy, innovation, and behavioral change.

Financial literacy has thus become a shared responsibility, essential for both individual stability and the public good It determines citizens’ ability to navigate a complex financial landscape, to build stability, and to make decisions that strengthen not only personal but also collective well-being. In the context of accelerated digitalization, growing social inequality, and intensified economic fluctuations, financial literacy is becoming a strategic resource for sustainable development.

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) today stands at a crossroads between rapid catching-up and structural vulnerability. While a number of Western European countries have long integrated financial education into their national curricula, in most CEE countries financial literacy remains marginalized – limited to campaigns and fragmented initiatives. This has left significant gaps in citizens’ financial behavior, and as a result many people now face challenges such as over-indebtedness, financial fraud, and difficulty assessing risk.

Europe’s New Financial Literacy Strategy

On September 30, 2025, the European Commission presented a package of initiatives marking a turning point in financial literacy policy within the European Union. It includes a European Strategy for Lifelong Financial Literacy and a blueprint for Savings & Investment Accounts (SIA) – a new instrument designed to encourage household participation in capital markets and to link education with real opportunities for action.

In presenting the strategy, Maria Luís Albuquerque, Commissioner for Financial Stability, Financial Services and the Capital Markets Union , emphasized that “financial literacy is no longer merely a matter of consumer protection, but a matter of economic autonomy.” Her focus on “the ability of every citizen to understand and manage their own financial reality” reflects the core philosophy of the new framework.

The new European policy places financial literacy at the heart of citizens’ economic autonomy, treating it as a system of social capital rather than a peripheral educational discipline. It views financial knowledge as an individual asset, but also as a collective factor for competitiveness, sustainability, and social cohesion.

Financial illiteracy, by contrast, has a measurable cost. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), each point lower in the financial competence index increases the likelihood of over-indebtedness, lack of insurance coverage, and inability to cope with unexpected expenses.1 In CEE, this effect is amplified by specific historical factors – a dominant deposit culture, low trust in capital markets, and limited access to financial education.

Beyond Savings – Financial Literacy 2.0 Financial literacy today is not only about knowing how to save but about understanding how to participate. From digital wallets and BNPL models to crypto-assets and algorithmic recommendations, financial decisions are increasingly shaped by technology and behavioral design. This “Financial Literacy 2.0” paradigm represents competence in action – the ability to make informed and responsible choices in a digital economy. It is an invitation to shift from passive saving to active, conscious participation in financial life.The package of 30 September 2025 outlines a new approach that combines knowledge andpractical tools. The new European Strategy for Lifelong Financial Literacy seeks to link education with practical mechanisms of participation rather than remain within theoretical frameworks. Alongside it, Savings & Investment Accounts (SIA) aim to create an accessible and transparent pathway to capital markets for ordinary citizens.

The European Commission’s document defines them as “a unified, transparent, and voluntary channel for household saving and investment,” which can be adapted to national tax regimes.³ The model is inspired by the UK’s Individual Savings Accounts (ISA) and by the EU’s Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP). Their goal is simple – to eliminate the main barriers facing retail investors: the complexity of products, administrative and tax burdens, and the lack of access to understandable market information. Thus, a cycle is created in which education leads to participation, and participation reinforces education. The Commission emphasizes that “financial literacy cannot be sustainable without a pathway for applying the knowledge acquired.”⁴

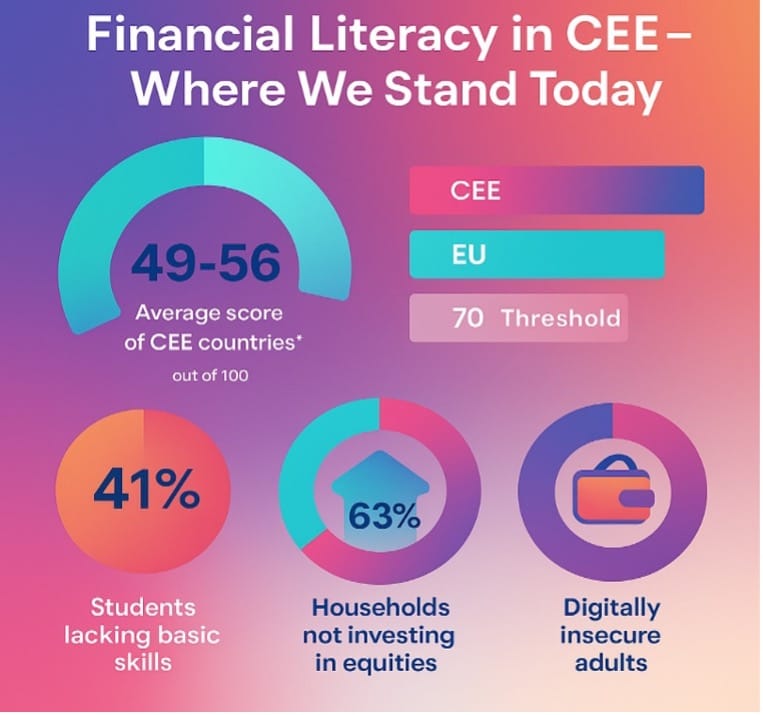

Figure 1. Financial Literacy Levels Across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)

Source: OECD/INFE, European Commission, author’s calculations.

In this context, SIA fit into the broader vision of the Capital Markets Union (CMU) — a strategic EU initiative aimed at deepening the integration of European financial systems and channeling private savings into investment in the real economy. For the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), this opens a window of opportunities but also presents challenges: the region accounts for 17% of the Union’s population, but less than 6% of market capitalization. The share of households investing in shares or funds remains two to three times lower than in Western Europe.⁵ This is not the result of a lack of income but of the absence of habit and an investment culture — a habit that can be built only through a consistent educational infrastructure and an enabling environment.

Financial Literacy in the Digital Era

This connection between policy, education and behavior is also confirmed by international indicators of financial literacy. Studies by the OECD, the World Bank and the FINRA Foundation show that financial knowledge is now assessed not merely by learned concepts, but by citizens’ ability to act rationally in an environment of informational noise, digital interfaces and uncertainty. According to the OECD’s 2023 international survey on adult financial literacy, only about 34% of adults in participating countries reached the minimum competency threshold of 70 points out of 100. This global benchmark highlights how financial understanding remains limited even in advanced economies, reinforcing the urgency of improving both knowledge and practical skills. The new Toolkit 2025–2027 of OECD/INFE, on the other hand, measures three key dimensions: digital financial literacy (the ability to safely use online banking, BNPL and crypto services); financial resilience (the ability to respond to inflation and unexpected expenses); and psychological maturity (trust, risk tolerance and critical thinking).

The latest results from 2023 are telling – only 29% of adults worldwide reach the threshold score of 70 points for adequate financial literacy, while the average score for CEE countries varies between 49 and 56 points compared to an EU average of 62.2 These figures do not reflect a lack of education, but a lack of coordination among the institutions that should build financial culture: schools, regulators, media and market participants.

A similar trend is observed in the PISA 2022 study, which assesses the financial skills of fifteen-year-old students. On average, one in four cannot solve a task related to percentage or interest, while in CEE countries this share reaches 41%.3 Poland represents a clear exception – thanks to the introduction of a mandatory financial education module as early as 2013, the country achieves an average index of 510 points, while Bulgaria remains at 440. This clearly proves that financial literacy is not a consequence of income, but of institutional will.

At the same time, data from Global Findex 2025 show that 79% of adults worldwide already have a bank or mobile account (90% in Europe and Central Asia), but only half feel confident using digital banking.4 Women and people from rural areas remain the most vulnerable, with only 47% of women in CEE describing themselves as digitally confident, compared to 63% of men.5 This difference underlines that financial inclusion is not only a matter of access, but also of trust.

Another important perspective is provided by the NFCS 2025 study by the FINRA Foundation, which for the first time introduces the themes of artificial intelligence and BNPL services into the analysis of financial behavior. More than half of respondents cannot calculate the real value of money at an inflation rate of 10%, and more than one-third use “buy now, pay later” services without understanding the full cost of the credit.6 For CEE, where digitalization outpaces critical thinking, this is a warning signal: if people’s critical thinking doesn’t keep up with technological progress, it can create a new form of vulnerability.

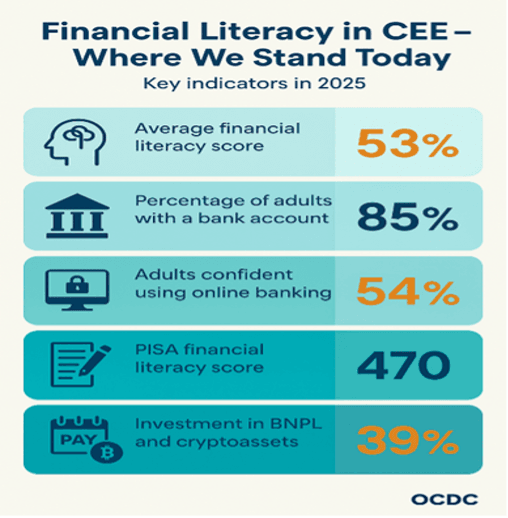

Key Financial Literacy Indicators Across Central and Eastern Europe (2025)

Source: OECD/INFE, World Bank, FINRA Foundation, author’s calculations

Ultimately, all these studies lead to one conclusion – financial literacy is not an isolated discipline but a combination of cognitive, social, and behavioral abilities that determine the quality of participation in economic life. For Central and Eastern Europe, this participation is yet to fully unfold.

Therefore, when we speak about financial literacy today, we can no longer confine it merely to knowledge or behavior. New technologies are transforming the way people perceive and apply financial principles, demanding a new framework of understanding – one that unites cognitive, social, and digital skills into a single whole.

Financial literacy can no longer be viewed separately from digital competence. Technology has changed not only the way people save and invest but also how they perceive risk, trust, and the very notion of financial responsibility. Within a decade, digital platforms — from mobile banking and investment applications to “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) services, crypto-assets, and algorithmic advisors — have created a new environment where decisions are made instantly, often influenced by interface design and behavioral mechanisms embedded in the technology itself. Such transformation raises the question of what it means to be financially literate in the digital age. If traditional literacy implied an understanding of concepts such as interest, risk, and return, then modern “Financial Literacy 2.0” requires critical thinking skills, comprehension of algorithmic processes, and awareness of the cognitive traps that the digital environment can create.

Emerging Challenges: BNPL, Crypto, and Financial Influencers

A telling example of this is the rise of BNPL services, which by 2025 have become one of the most dynamic trends in European markets. According to the OECD/INFE brief from September 2025, these products create an “illusion of liquidity,” allowing consumers to make installment-based purchases through intermediary platforms without realizing the accumulation of microcredits beyond the control of credit registries.7 Data from the European Consumer Organisation (BEUC) shows that Central and Eastern Europe is among the fastest-growing BNPL markets, particularly in Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria.8 Paradoxically, these are precisely the countries with lower levels of financial literacy and weak credit behavior culture. The OECD recommends introducing clear warnings within consumer interfaces visualizing the actual annual percentage rate (APR) and including such microcredits in national registries. This measure is not merely administrative — it also carries educational potential, as it compels the consumer to reflect on their decision before confirming a purchase.

A similar risk of misinterpreting information is also observed in the case of crypto-assets. The new OECD/INFE brief for 2025 shows that only 41% of crypto investors in developed economies are aware that cryptocurrencies are not legal tender, and less than one-third understand the tax implications of trading them.9 In Central and Eastern Europe, interest in crypto-assets is even higher than the EU average: between 12% and 16% of the population in Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland have purchased cryptocurrency at least once. The reason is not merely technological curiosity but also distrust toward traditional financial intermediaries. This dynamic highlights a new form of “digital illusion of autonomy” — the perception that digital access automatically implies competence.

Regulatory authorities in the region are beginning to respond proactively. In Poland, the Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) expanded its educational platform CEDUR with the course “Invest Cautiously,” which includes modules on crypto risks and the taxation of digital assets. In Bulgaria, the Financial Supervision Commission launched the campaign “Money and Tokens” in March 2025, targeting young investors and explaining the principles of the MiCA regulation. Such initiatives demonstrate that effective supervision is not merely punitive but also an educational instrument that builds a culture of understanding before participation.

Equally significant is the issue of artificial intelligence and its impact on financial behavior. The FINRA Foundation’s July 2025 study reveals that more than two-thirds of respondents perceive algorithmic recommendations as “objective,” without realizing that these systems reflect pre-defined commercial interests.10 In an era where algorithms personalize credit offers, investment decisions, and even insurance products, the lack of understanding of their mechanisms turns the consumer into a passive object rather than an active subject of their own choices. The OECD calls for the introduction of “algorithmic literacy” programs in universities and vocational schools as part of modern financial education. In the context of CEE, where the fintech sector is growing by more than 20% annually, such an initiative would be crucial for building cognitive filters against manipulative algorithms.

At the same time, a new phenomenon is emerging — so-called “finfluencers.” Social networks such as TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram have become the main source of financial content for younger generations, but also a breeding ground for misinformation. According to ESMA’s 2025 analysis, more than one-quarter of young investors in the EU admit that they make investment decisions under the influence of such content.11 What is more, A Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission (CySEC) survey (2023) found that nearly 22% of retail investors make investment decisions based on social media promotions or celebrity endorsements. The effect is doubly dangerous: not only because the content is often sponsored and unregulated, but also because its emotional format creates an illusion of closeness and accessibility. The European Commission is discussing the introduction of a “Verified Finfluencer” label — similar to the “EU Ecolabel” — to certify the reliability of authors providing financial content. For CEE, where social networks are often the first channel for accessing investment information, such an initiative could have an immensely educational impact.

In summary, all these trends outline the contours of a new financial literacy — one that goes beyond technical knowledge and becomes a behavioral and ethical competence. Being financially literate today means not just understanding market mechanisms but being able to recognize manipulation, evaluate the credibility of information, and find balance between the speed of technology and the rationality of human decision-making. As summarized in the latest OECD/INFE report:

*“Digital financial literacy is no longer a luxury; it is the baseline competence for democratic and economic participation.”*12

For the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, this requires a transition from imitation to conscious participation. The region does not suffer from a lack of technology, but from a critical evaluation skills. The introduction of financial education adapted to the digital reality is no longer merely an educational matter, but an economic necessity – a prerequisite for the sustainability of societies in an increasingly algorithmic economy.

Financial Literacy 2.0 requires the countries of Central and Eastern Europe to move from imitation to conscious participation. The region does not lack technology but rather cognitive filters that enable critical thinking and responsible decision-making in a digital environment. The implementation of financial education adapted to the realities of the new economy is no longer just an educational priority, but an economic necessity. Here lies the next challenge – how this transformation of knowledge can become a structural factor for growth and trust in Central and Eastern Europe.

Closing the Financial Literacy Gap in CEE

According to Eurostat data, household financial assets in the European Union amounted to €37.3 trillion in 2023, but the share of directly held equities remains extremely low.13 The analysis by AFG and OEE (2025) shows that only around 6% of household assets in the euro area are in the form of direct shares, while the rest are held through pension and insurance products. In the CEE countries, this share is even lower — not due to a lack of capital, but due to a lack of trust and financial confidence.

Data from Global Findex 2025 confirm that between 87% and 95% of adults in the region already have a bank or mobile account, but only 7% to 23% invest in stocks or funds.14 This gap between access to financial infrastructure and actual participation in capital markets clearly shows where the main barrier to development lies — not in technology or institutions, but in behavior.

Distrust remains a systemic problem that undermines economic activity and discourages citizens from participation. The ESMA (2025) study on the “retail investor journey” shows that the main barriers are fear of fraud, product complexity, and low self-assessment of financial competence.15 In Bulgaria and Romania, more than 60% of respondents state that they do not invest because they “do not understand enough,” while in Poland this share drops below 40%. Increasing knowledge leads not only to more informed decisions but also to a greater willingness to participate — in pension schemes, collective investment funds, and innovative financial instruments. In this sense, financial literacy becomes the capital of trust – an invisible but decisive resource for economic resilience.

The development of national policies in this direction shows an interesting evolution. In Poland, the Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) has been building the CEDUR platform since 2010 – a long-term program for investor education and protection aimed at students, teachers, and young entrepreneurs. In 2024–2025, the program includes a “Polish Investor” module that uses simulations and online seminars to promote long-term saving and risk awareness. In Romania, ASF (Autoritatea de Supraveghere Financiară) and ISF (Institute for Financial Studies) organize campaigns such as Global Money Week and the White Day of Universities, which connect the academic community with real market participants. Bulgaria has also made progress: in June 2025, the country adopted the Law on Crypto-Assets, transposing the MiCA regulation and strengthening consumer protection. This opened the door for new educational initiatives, including the Financial Supervision Commission’s campaign “Money and Tokens,” aimed at clarifying the difference between regulated and unregulated assets.

Although the region is heterogeneous in terms of economic structure, these examples demonstrate a common trend – a shift from one-time campaigns to long-term programs integrated into the policies of supervisory and educational institutions. This means that financial literacy is gradually ceasing to be a peripheral activity and is becoming a strategic priority for national financial stability.

The macroeconomic perspective confirms this process. According to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), CEE economies will grow by around 3% annually but will remain exposed to inflationary pressures and external shocks.16 In this context, domestic savings must be transformed into investments — a goal that can only be achieved through higher financial literacy and the creation of incentives for citizens to participate in capital markets. This is precisely where the European Commission’s package of September 30, 2025 — including the Financial Literacy Strategy and the Savings & Investment Accounts (SIA) — acquires a dual role: both educational and economic.17

Figure 3. Key Indicators of Financial Literacy and Inclusion in Central and Eastern Europe (2025)

| Indicator (2025) | Bulgaria | Romania | Poland | Croatia | Slovenia |

| Adults with bank or mobile account | 87 % | 85 % | 95 % | 91 % | 97 % |

| Households investing in equities/funds | 7 % | 8 % | 23 % | 18 % | 27 % |

| Average financial literacy score (OECD/INFE 2023) | 52 | 50 | 56 | 54 | 61 |

| Gender gap in financial confidence (women–men) | –17 p.p. | –16 p.p. | –9 p.p. | –12 p.p. | –7 p.p. |

| Participation in financial education programmes | partial | limited | national strategy | partial | integrated |

| BNPL usage (2025) | 24 % | 27 % | 31 % | 22 % | 20 % |

Source: World Bank (2025); OECD/INFE (2023); ECB (2025); ESMA (2025).

The visual data confirm the main conclusion: the gap between access and participation remains the most significant challenge for the region. Financial literacy in CEE is still not sufficient to turn economic potential into real investment activity, but the trend is clearly positive. The combination of educational policies, digital transformation, and new incentives such as the SIA can serve as a catalyst for deeper market participation and a more resilient economic culture.

Achieving these goals requires consistency, measurability, and supranational coordination. But even more importantly, it requires the understanding that financial literacy is not merely a political instrument, but a cultural transformation – a change in the way societies think about risk, time, and value. This is the true role of financial education: not to create investors by compulsion, but citizens with confidence and economic dignity.

In Europe’s post-crisis era, financial literacy becomes an institutional imperative – the foundation of economic stability and social cohesion. For the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, this process carries particular significance: the region has a historic opportunity to use digitalization as a catalyst for inclusion, but only if knowledge is transformed into real competence and trust.

“Beyond Sa